Identity and Roles in Antiquity

The Muses of Greek mythology were goddesses of poetry, song, and dance and are unparalleled in any other part of the world. They are likened to Nymphs, Charites (Graces), and Sirens as they are all highly skilled in song and/or dance. They represented practice, memory, and song (Melete, Mneme, and Aoide) which happen to also be the names of the Muses in one of the many versions of their identity. Hardie (2006) elaborates on them in this regard as follows:

“The techne of memorisation appeared in the early fifth century and was elaborated later as a rhetorical discipline. It had to do with developing the memory, through practice (melete), to cope with the professional demands on poets and speakers, including improvised response to occasion. Improvisation although re-invented as a product of sophistic techne, was a link between the disciplines, skills and memory of the aoidos who might be required to sing to demand (or to respond to occasion), and those of the prose speaker. A wider debate about memory, writing and mnemomics explored the individual’s natural capacity for recall versus artificial mnemonic stimuli to memory; as also the individual’s inner capacity for memory versus the external stimuli to memory provided by written texts.”

MediaWiki

As the divinities of these aspects of the arts, the Muses had the power to grant and take away the skill of an artist, whether it be voice or memory.

The Muses were most often imagined as a group of three as they were closely associated with other trios of female divinities; “…discussion of the Muses of Helicon, lists partly analogous female divinities from the neighboring area of Boeotia: the three Charites of Orchomenos, the Sphragitid Nymphs of Mount Cithairon, the Three Maidens of Eleon east of Thebes, the Muses of Mount Thourion outside Chaironeia, and the Leibethrian Nymphs” (Maslov, 2016). The development of the nine Muses could well have been because of their similarity to the function of the real life maiden chorus who performed in plays acting as a sort of narrator.

Jacopo Tintoretto – The Muses, 1578

The Muses acted as guides who gave inspiration to writers including poets, musicians, and philosophers. Often at the beginning of their works, writers would call upon the Muses to guide them in their writing or even offer themselves as a method through which the Muses could speak and share their wisdom and memory. This practice also served a practical purpose. As literature was commonly performed in song, talking to the Muses offered a break in which the performer could recall the next lines while simultaneously asking the Muses for aid in remembering long, complex verses. For example, in the following passage from the Iliad the bard recognizes that he needs help in remembering a list of names:

Tell me now, you Muses, who have your homes on Olympos

For you, who are goddesses, are there, and you know all things,

and we have heard only the rumour of it and know nothing.

Who then of those were the chief men and the lords of the Danaans?

I could not tell over the multitude of them or name them,

not if I had ten tongues and ten mouths, not if I had

a voice never to be broken and a heart of bronze within me,

not unless the Muses of Olympia, daughters

of Zeus of the aegis, remembered all those who came beneath Ilion.

(Iliad, 2.484-92)

Homer also uses the Muses as a tool to build suspense. As the tension mounts in book 11 of the Iliad we learn that Agamemnon is about to be struck by a spear and in the height of our expectation for action there is a pause to consult the Muses, thereby teasing the audience:

So the fighting grew close and they faced each other, and foremost

Agamemnon drove on, trying to fight far ahead of all others.

Tell me now, you Muses who have your homes on Olympos,

who Each Musewas the first to come forth and stand against Agamemnon . . .

(Iliad, 11.216-19)

We know this teasing phenomenon to be the case, as opposed to asking for help with memory, because instead of asking for a list of names he is only asking for one, which he could surely remember. Additionally, when Homer does this it is always right before a scene of exciting action.

MediaWiki

In order for a performance to be taken as truthful, or at least accurate, the bard or author of the piece being performed had to have some connection to the events within, whether that be by first, or second-hand account, or by a metaphorical ‘stamp of approval’ by the Muses. If the performer is believed to be speaking truth inspired by the gods, the invocation of the Muses is an assurance of authenticity. Thus the Muses, or sometimes Apollo, come to be, at the very least, partly responsible for the quality of storytelling, singing, music, and validity of the content. Therefore, as Homer addresses them throughout the Iliad before lists and major events he reassures the audience that these stories are true while giving his work as a whole divine authenticity.

Origins

There are many different origin stories of the Muses and various groups of ancient people disagreed on how many Muses there were and from where they originated. They were thought to be sisters numbering in three (from our earliest sources) or nine (a development of the late Classical Age) with varying names and parents, thought to be of either Thracian or Boeotian origin. According to the poet Hesiod the nine Muses originated on the Greek mainland in Boeotia, the children of the Olympian god Zeus and the young goddess Mnemosyne. Mnemosyne was the daughter of the two Titans Uranus (who personified the sky), and Gaia, the mother of the universe. In his predictable fashion, Zeus disguised himself as a shepard in order to woo Mnemosyne and slept with her for nine consecutive nights, resulting in the conception of the nine Muses. When they were born they were given to the nymph Euphime and the god Apollo who taught them the arts, in which they showed great interest and skill, while having no interest in the activities of daily life. Apollo brought them to the Temple of Zeus on Mount Helicon where they dedicated their lives to the encouragement of creation, imagination, and the inspiration of artists.

Alberto Fernandez. MediaWiki

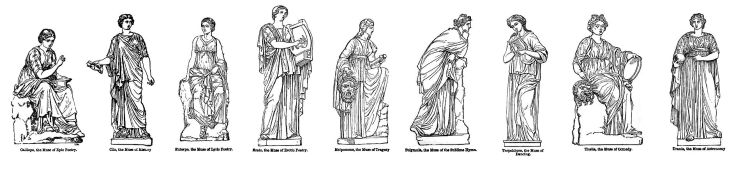

Each Muse represented or embodied a different artistic form and had various items associated with them according to their art: Urania, the Celestial One – astronomy, globe and compass; Thalia, the Flourishing or Blossoming One – comedy, comic mask, shepard’s hook, and ivy wreath; Terpsichore – dance, lyre and plectrum; Polyhymnia, the Singer of Many Hymns – hymns, veil and grapes; Melpomene, the Chanting One – tragedy, tragic mask, sword, club, and kothornos (boots); Erato, the Passionate or Lovely – love poetry, cithara; Euterpe, the One Who Rejoices Well – music, song, and lyric poetry, aulos (flute), panpipes, and laurel wreath; Clio, the Proclaimer – history, scrolls, book, cornet, and laurel wreath; Calliope – epic poetry, writing tablet, stylus, and lyre.

Another origin story of the Muses is that Pegasus touched his hooves to the ground at Helicon where four springs burst forth, from which the Muses were born. Athena later tamed the horse and presented him to the Muses. The Muses are heavily associated with Helicon and its springs, which is part of the reason that they are sometimes thought of as water nymphs.

Jacques Lipchitz, Birth of the Muses (1944-1950), Massachusetts Institute of Technology Campus, Cambridge, Massachusetts. MediaWiki

Myth

The Muses were not always the innocent, ethereal women of myth that we think of today. They have episodes where they show how proud and unforgiving they can be. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses there was a king named Pierus of Macedon who had nine daughters which he named after the Muses. King Pierus believed that his daughters had enough musical skill to be a match for the Muses and so challenged them to a competition. Unsurprisingly, the Muses won and as punishment for this act of hubris, turned the king’s daughters into magpies. Similarly, the Thracian singer Thamyris challenged the Muses and lost, this time the punishment was blindness and the loss of his singing ability.

As for their role as characters in literature, they usually do not affect the plot but appear in emotional episodes and act to evoke strong feelings and tears from the audience. In the Odyssey, for example, they appear to mourn the death of Achilles:

And all the Nine Muses in sweet antiphonal singing

mourned you, nor would you have seen any one of the Argives not in tears,

so much did the singing Muse stir them.

(Odyssey, 24.60-62)

In the Iliad and the Odyssey the Muses main function in the narrative is in their relationship to the bard himself.

Significance in Art

The Muses have inspired sculpture, painting, and all types of art through the ages. They occupy many Greek artifacts in the form of relief, Renaissance art featured the Muses, among other ancient Greek deities, heavily, they are featured in the modern Disney movie Hercules, and there is even a band called Muse. They even remain in our language as “museum”, “music”, and “amuse” are directly derived from these ancient goddesses.

References

Beloff, R. (2015, Sep 24). Sweet september. Jerusalem Post Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.mta.ca/docview/1721193610?accountid=12599

Cole, J. (1997). The Muses of Homer and Hesiod: Comparative Musings. Scholia: Studies in Classical Antiquity, 6, 168-177. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.mta.ca/docview/211600833?accountid=12599

Hardie, A. (2006). The aloades on helicon: Music, territory and cosmic order. Antike Und Abendland, 52, 42-71. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.mta.ca/docview/229999345? accountid=12599

Homer. (2009). The Iliad (M. Mueller, Trans.). London: Bristol Classical Press.

Homer. (1996). The Odyssey (E. V. Rieu, Ed.). London: Penguin Books.

Maslov, B. (2016, August 25). The Genealogy of the Muses: An Internal Reconstruction of Archaic Greek Metapoetics. Retrieved March, from http://muse.jhu.edu/article/629220

Ovid. (1994). Metamorphoses (F. J. Miller & G. P. Goold, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Origins. (2005, 09). Writing, 28, 6. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.mta.ca/docview/196501803?accountid=12599

2 thoughts on “The Muses”