In Greek mythology, Hestia is the little known twelfth Olympian and is the goddess of the Hearth. Throughout the Greek and Roman era (where she was known as Vesta) Hestia played an important role in the daily lives of most people, being especially important when it came to worship within one’s own home. Hestia’s contribution to society was ever present if often hidden just out of sight. In mythology, Hestia is tied closely to the home, as well as Hermes, in an interesting twist (the goddess of the hearth being associated with the god of travelers).

Below: Resting Hermes by Lysippos (Naples). Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011)

Hestia and Hermes were often associated with each other in Greek mythology. This was due to the idea that the two opposites of home and travel essentially balanced each other out. In his essay Hestia and Hermes: The Greek Imagination of Motion and Place Jean Robert explains that the two are “not husband and woman, nor brother and sister, nor mother and son” and that they are “neighbors, or better: friends” (Robert, Hestia and Hermes, 1996). Robert also states in his essay that “Where Hermes loiters is Hestia never far, and where Hestia stays, Hermes can appear at any moment”.

However, much of the mythology pertaining to Hestia focuses largely on her being a virgin goddess, being vital to maintaining the home and hearth and as, if not a role model, then somewhat of an analogy for Greek women during antiquity. By drawing on the work of various scholars, it is possible to gain insight into how Hestia played a role in the lives of ancient Greeks and especially in the lives of women.

Starting off, it is important to know the basics of who Hestia was. Hestia is the goddess of the hearth in Greek mythology and is one of the twelve Olympian gods. She was worshipped across Greece but was only worshipped in a cult setting in a small number of places. Worship of Hestia dates back to an early point in Greece’s history as she was already “firmly established as a goddess in Hesiod’s Theogony” (written around 700 BCE) (Kajava, Hestia, 2004). While Hestia is present in religion from an early point in Greece’s history, it is difficult to pin down the origin of Hestia interpreted as a goddess. This is because in the early days of Greece, Hestia was referred to by the same word and in much the same manner as the hearth itself.

Symbolism

While Hestia’s main symbol is the hearth, there are multiple ways that this symbol can be interpreted. These examples of symbolism range from more interpreting her virginity as reflecting the purity of fire, to her connection to the hearth being seen a sort of fertility. A theory by French scholar Jean-Pierre Vernant argues that Hestia represents a non-sexual type of fertility by her connection to the hearth. This ties into the fact that Hestia is occasionally associated with Aphrodite. While Hestia herself is a virgin goddess, she and Aphrodite can be seen as another pair of Olympians whose domains both conflict with and compliment one another.

Below: Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite, from Parthenon east pediment. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen

An photograph taken at the Parthenon, of a statue depicting Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite. Hestia is the figure on the far left.

Place Within Society

One major difference between Hestia and the majority of the Olympian gods comes from her function within society. Records of worship of Hestia make it clear that she was worshipped in private in people’s homes, but also that her worship was involved significantly with political matters in ancient Greece. A writing attributed to Dionysus of Halicarnassus states that the cult of Hestia was supervised by “those who have the supreme power in the polis” (Kajava, Hestia, 2004). This more formal worship of Hestia was centered around a common hearth known as the prytaneum. Each state had a prytaneum and fire would be taken from it to kindle the hearth of any now residences built within the state (Zekavat, Myths About the Origin of Fire, 2014). Due to the unconventional nature of Hestia’s half-political, half-religious significance, priests and priestesses in the traditional sense were essentially non-existent within cults of Hestia. In writings from antiquity, the only mention of a priest of Hestia that is actually referred to as a priest is thought to possibly be result of improperly restored writings.

Ancient Kassope – Prytaneum. Photograph by Harry Gouvas (2010)

An ancient prytaneum as seen in the modern day. One of the major places of worship for Hestia, it was also one of the few places around which anything resembling a cult routinely gathered.

An ancient prytaneum as seen in the modern day. One of the major places of worship for Hestia, it was also one of the few places around which anything resembling a cult routinely gathered.

Hestia’s personality is different from many of the Olympians due to her more pacifistic nature. During Plato’s time, there were arguments as to whether Hestia or Dionysus was the twelfth Olympian. For example, in Athens a depiction of all of the Olympians including Hestia could be found in the Agora, while a depiction of them including Dionysus but missing Hestia could be found on the east frieze of the Parthenon (Dorter, Imagery and Philosophy, 1971). This discrepancy, combined with the seeming lack of any substantial amount of mythology surrounding Hestia eventually saw Dionysus become the more consistently agreed upon twelfth Olympian. Some scholars see this is being representative of Hestia’s “non-confrontational nature – by giving her Olympian seat to the more forceful Dionysus” (Kerenyi, The Gods of the Greeks, 1951). Whether or not this is the case is difficult to say due to lack of evidence, though it is clear that something or other occurred to make Dionysus more accepted as the twelfth Olympian than Hestia.

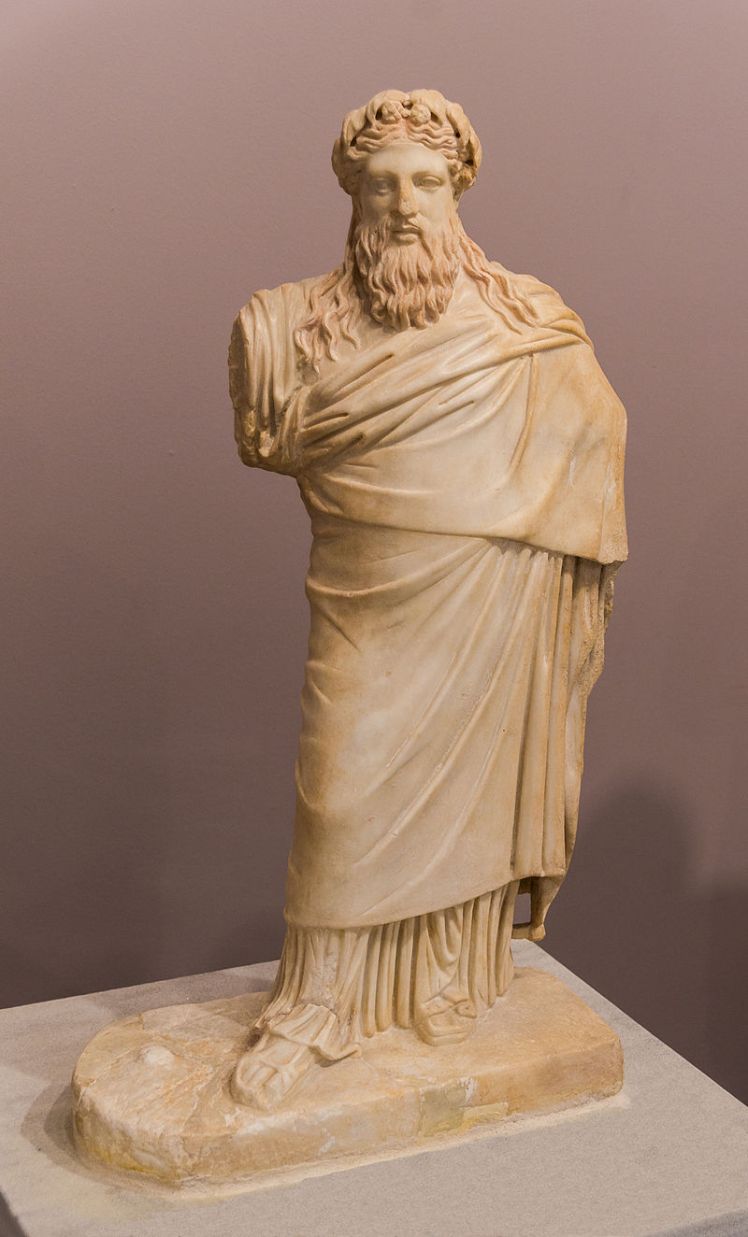

Below: Small statue of Dionysus made by Praxiteles (circa 300 BCE). Photograph by Wikimedia Commons user Jebulon (2015)

A small sculpture depicting Dionysus.

There are some potential explanations for why this is. When taking into account what both Olympians represented, there is a clear difference not only in their personality, but what they expect from worshipers. Whereas worship of Hestia was performed at home and more of a small, formal offering, Dionysus’ domain included the likes of theater, symposia, and for the most part, general merry-making. While more serious worship was performed at sanctuaries and temples, Dionysus had something that Hestia did not in the form of joyous social gatherings. It is not out of the question that this could have played a part in Dionysus taking the place of the twelfth Olympian while Hestia faded into the background and out of the history books.

What We Know

Moving from information about Hestia herself to the study of mythology surrounding her, it quickly becomes apparent there is a significant lack of research on the subject. Papers that mention her often only cite her as a passing name, or as one of the virgin goddesses while examining them as a group rather than Hestia herself. In many respects, she is the forgotten Olympian. Left by the wayside while practically every god and goddess save for possibly Demeter and Dionysus steal the spotlight. As such, much of the art and sculptures depicting Hestia have been lost to time, even more so than most art from Ancient Greece. Whether due to this, or for the sake of consistency, the vast majority of images of Hestia depict her in one specific pose, with her right hand on her hip, and her left hand pointing roughly up and forwards. It is uncertain as to whether this pose has any significance or whether it was simply that of one of the few surviving sculptures from antiquity.

Statue of Hestia. Margaret Clapp Library, Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts, USA

Though this particular statue of Hestia was made in the modern era, it maintains the iconic pose that so many depictions of the goddess share.

What We Don’t Know

Another aspect to examine are the specifics of the papers themselves. To begin, only one of them is less than a decade old. While this would not be as much of an issue in a course studying the ancient world in general, in a course such as this, where the focus is on the women of the ancient world, it becomes more and more difficult to find information about a topic like Hestia. While archeologists may have been studying artifacts and writings from ancient Greece and Rome for over a century, the way archeologists view antiquity has changed drastically. Archeologists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were very conscious of the fact that they were only as good as their greatest discovery. Artifacts and writings that could draw a reaction from the masses back in Europe would be more likely to cement an archeologist’s name in the history books, or at least the front-page news.

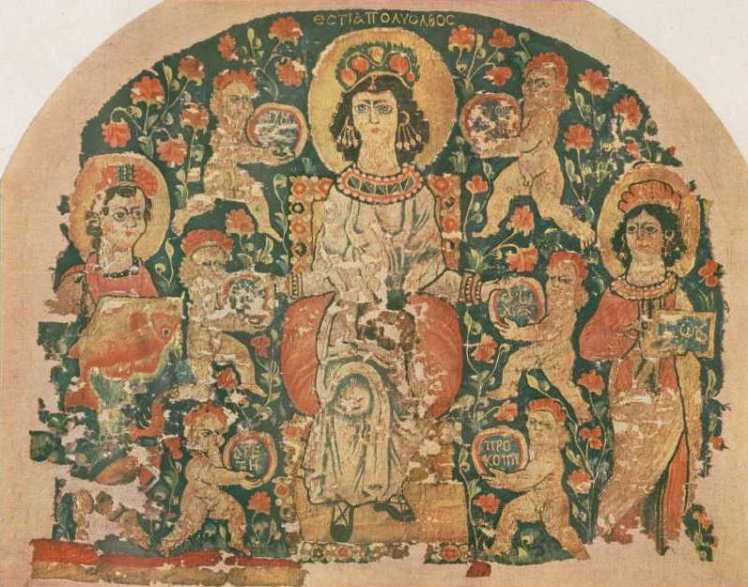

Below: Greek Goddess Hestia. Illustration from der Mythologie aller Völker by Dr. Vollmers Wörterbuch (1874)

An illustration of Hestia in her iconic (if nearly her only) pose. Searching for images of Hestia brings up relatively few results, many of which are near perfect doppelgangers of the above image.

This issue applies not only to research about Hestia though. As mentioned before, with so few surviving artifacts associated with Hestia, relatively little is known about how else she may have been depicted besides the above image. Given how her name was, at one time, synonymous with the hearth she represents, it stands to reason that she may have been depicted in various ways over the course of Greek history. Because of this, along with the tendency of other Olympians to assume various guises throughout mythology, the lack of any evidence of such portrayals of Hestia seem to point more to lack of information rather than having not existed. Hestia is known through just a handful of sources, and from that archaeologists have had to piece together as much as they can on a goddess who, in reality, holds the title of the eldest Olympian. What information remains points to her being worshiped practically everywhere in Greece, likely every day, and yet there is so little known about her.

Despite what fragmented information in known about Hestia (as compared to other Olympians at least) it is clear that she influenced a number of different areas of ancient Greek society. She was a religious symbol both at home and at certain community gatherings. She was worshipped by everyone regardless of social standing; whether it was an average person dedicating food at the hearth or those in charge of the prytaneum organizing the transferral of a flame from the prytaneum to a new house. She was depicted as being above the constant infighting typical of the other Olympians, and overall gives the impression that there is so much more to learn about her. Whether archaeologists ever uncover such evidence is anyone’s guess. If the do though, it could mean a brand new insight into the history of the last Olympian.

Resources

“Dionysus.” Wikimedia Commons. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2017.

Dorter, K. (1971). Imagery and Philosophy in Plato’s Phaedrus. Journal of the History of Philosophy,9(3).

“Hermes.” Wikimedia Commons. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2017.

“Hestia.” Wikimedia Commons. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2017.

Kajava, M. (2004). Hestia: Hearth, Goddess, and Cult. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology,102, 1-20.

Kerenyi, K. (1951). The Gods of the Greeks.

“Prytaneum.” Wikimedia Commons. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2017.

Robert, J. (1996). Hestia and Hermes: the Greek imagination of motion and place.

Walcot, P. (1984). Greek Attitudes Towards Women: The Mythological Evidence. Greece & Rome,31(1).

Zekavat, M. (2014). Ecocriticism and Persian and Greek Myths about the Origin of Fire. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture,16(4).

This article is so beautifully written! It flows so nicely, I love it! The information is presented very well. It’s unfortunate that there isn’t more information on Hestia for you but you did a great job at explaining everything despite that. The way you showed the comparisons to the other gods she hung out with really added to this page. I find it interesting that she is tied to Hermes. Perhaps this could show how people are supposed to be welcoming to travellers? Her signature pose almost seems like she’s welcoming you, or asking you to come in for tea or something. Overall, I really enjoyed this article. Good job!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. What about the “vestal virgins”? I know that is Roman but if Vesta is Hestia can that shed more light on her?

LikeLike