Across most cultures and time periods, not only does bridal attire play a significant role in the wedding ceremonies, but they contain important symbolic messages as well (Llewellyn-Jones, 2003). Ancient Greece and Rome were no exceptions to this rule and marriages had great significance in a woman’s lifetime. A combination of different literary and iconographic evidence offers an extensive description of bridal attire from antiquity. Furthermore, the symbolisms that are embedded in the bridal attire of antiquity are deeply connected to how the ancient Greek and Roman societies viewed women and marriage.

Bridal Attire in Ancient Literature

A number of ancient literary sources, such as Pliny’s The Natural History, Achilles’ Leucippe and Clitophon, and Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days, offer insights for the appearances of Greek and Roman brides on their wedding days. While each excerpt only explains or refers to the bridal attire briefly, a combination of these different literary sources offers a more accurate and detailed portrayal of bride attire in antiquity.

Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days

In Hesiod’s Theogony, he recounts the anger of Zeus as a result of Prometheus stealing the fire. Therefore, Pandora was created as a punishment to mankind and Hesiod portrays this character through the context of marriage. He also specifically states how Pandora is dressed:

. . . Athena, girdled and adorned her with silvery clothing, and with her hands she hung a highly wrought veil from her head, a wonder to see; and around her head Pallas Athena placed freshly budding garlands that arouse desire, the flowers of meadow; and around her head she placed a golden headband . . . (573-578)

The discussion of Pandora’s outfit appears again in another work by Hesoid, Works and Days (Hesiodus, 2005):

. . . the goddess bright-eyed Athena gave her a girdle and ornaments; the goddess Graces and queenly Persuasion placed golden jewelry all around on her body; the beautiful-haired Seasons crowned her all around with spring flowers; and Pallas Athena fitted the whole ornamentation on her body. (72-7)

Both passages present detailed imageries that demonstrate how Pandora is dressed. For instance, in Theogony, Pandora is depicted wearing a silver attire, a veil, a flower garland, and a golden headband. The description of flower and jewelry as parts of her attire appears again in Works and Days. In Theogony, since Pandora was presented through the context of marriage, the attire she wore may be a reflection of the bridal attire in ancient Greece. For example, Llewellyn-Jones (2003), argues that it is possible that Hesoid’s “references to the wedding veil and to the desirable female qualities evoked by veiling might be regarded as an accurate representation of the use of the veil in his own contemporary community” (p. 137).

A contemporary artistic depiction of how Pandora was created and dressed.

However, because both of these texts are mythological in nature, certain elements of the bridal attire may have been exaggerated as they can be enhanced by the power from divinities. Therefore, while these two passages offer detailed descriptions of the bridal attire in antiquity, one must also consider how precisely they reflect the reality in ancient Greece, particularly for the women of lower socio-economic status.

Achilles’ Leucippe and Clitophon

Another work that provides a detailed depiction of the bridal attire in Ancient Greece is Leucippe and Clitophon, a romance written by Achilles Tatius (Hadas, 1950). At the beginning of the work, Clitophon falls in love with Leucippe while being already engaged to his half-sister, Calligone. In an excerpt from the work, Achilles offers a description of the bridal attire that is prepared for Calligone:

All the bridal ornaments had been bought for the maiden: she had a necklace of various precious stones and a dress of which the whole ground was purple; where, on ordinary dresses there would be braidings of purple, on this they were of gold. In the necklace the gems seemed at rivalry with one another; there was a jacinth that might be described as a rose crystallized in stone and an amethyst that shone so brightly that it seemed akin to gold ; in between were three stones of graded colours, all mounted together, forming a gem black at the base, white streaked with black in the middle, and the white shaded oft’ into red at the top: the whole jewel was encircled with gold and presented the appearance of a golden eye. As for the dress, the purple with which it was dyed was no casual tint, but that kind which (according to the story the Tyrians tell) was discovered by the shep- herd’s dog, with which they dye Aphrodite’s robe . . . (2.11)

What remains consistent between this passage and Hesiod’s is the use of jewelry in the bridal outfit. Since both of the excerpts offer descriptions detailing the lavish use of precious metal and gemstones and the attention to details when preparing the bride for her wedding, it implies that the bridal attire was a significant piece of clothing in the culture of ancient Greek. Moreover, the shade of purple in this context is specified to be the same as the one that is used to dye the robe of Aphrodite. Oakley and Sinos (1930) suggest that the association between bridal attire and Aphrodite is significant as she is the goddess of sexual love. Thus, the reference to Aphrodite represents the sexuality of the bride and just like the gold jewelry, along with the other components of the bridal attire, is meant to present the bride as an attractive woman who is no longer a child (Oakley & Sinos, 1930).

On the other hand, as opposed to silver being the color of choice for the bridal attire as described by Hesoid, the color of the dress in this excerpt is purple. Furthermore, since the iconographic evidence on this topic comes from red-figure potteries, the exact color of the Greek bridal attire remains to be a mystery.

Plutarch’s Roman Questions

One of the wedding traditions of ancient Rome in regards to the bridal attire is the parting of hair into six locks, perhaps using a tool named the celibate spear, hasta caelibaris in Latin (Hersch, 2014; Olson, 2008). Roman Questions is a collection of questions and answers on the topic of Roman customs, written by Plutarch (Babbitt, 1936). Question 87 from this work specifically deals with this specific wedding tradition.

Plutarch offers three possible answers to this custom. The first reason given illudes to the origin of the first Roman brides, the Sabine women (1936). These women originally lived beside Rome, but they were seized from their families by Roman men and forced into marriage with them. The purpose of these forced marriages was to ensure the purity of Rome’s first mothers (Fantham et al., 1994). Plutarch elaborates on this possibility and suggest that by using a spear, the brides are also demonstrating that they are learning to behave like their warrior husbands and live a life without extravagance. The second part of the answer is that divorce can be initiated by a sword. The third and the last suggestion is that this tradition is connected to the goddess, Juno, whose statues often depict her leaning on a spear (1936). Plutarch is perhaps referring to how one of the specific religious cults of Juno, named Juno Sospita, often depicts the goddess carrying a spear, a shield, and wearing goatskin. Plutarch possibly makes the connection between this wedding practice and Juno since she is the goddess of women (Rives, 2003).

Pliny’s The Natural History

Pliny the Elder suggested in his work, The Natural History, that the origin of the traditional attire of Roman brides could be traced back to the time of Etruscan dynasty (Plinius, 2007). He states that: “Marcus Varro informs us, on his own authority, that . . . . Tanaquil first wove a straight tunic of the kind that novices wear with the plain white toga, and newly married brides” (8.74.1-3). In this excerpt, Pliny the Elder cites another author, Varro, when explaining that the earliest version of a tunica recta, which later became the attire of Roman brides. He suggests that the tunic was first woven by Tanaquil, the wife of Tarquinius Priscus (Olsen, 2008). Therefore, this source provides insight into the possible origin of the Roman bridal attire and that their tradition could date back to around the 7th century BCE, the date when Tanaquil arrived in Rome along with her husband (Fantham, Foley, Kampen, Pomeroy, & Shapiro, 1994).

Catullus’s Epithalamium On Vinia And Manlius

Epithalamium On Vinia And Manlius is a poem written by Catullus about the wedding of Junia and her groom, Manlius. In the very beginning of this poem, Catullus describes how the god Hymen makes his appearance dressed as a bride:

About thy temples bind the bloom,

Of Marjoram flow’ret scented sweet;

Take flamey veil: glad hither come

Come hither borne by snow-hue’d feet

Wearing the saffron’d sock. (61)

This excerpt alludes to an essential part of the wedding attire in ancient Rome, flammeum, which refers to the veil worn by the brides. This piece of clothing, however, was not affordable for the majority of the Roman families. Instead, it was only part of the attire of brides who came from upper-class families (Olsen, 2008). However, the exact color of the veil cannot be pinpointed and the shade could possibly range from different tones of yellow to orange, or even pink (Olsen, 2008). This paragraph also states that brides would have worn special shoes in the color of saffron as explicitly described by the author. On the other hand, as argued by Hersch, no other Roman authors suggested that brides would wear special shoes in their writings (2014). Another piece of the bridal attire that is alluded to by this passage is the marjoram flowers worn on the brides’ head. More importantly, the association of god Hymen and the bridal attire is significant as it not only alludes to the virginal innocence of the bride but also her sexuality as the god represents the consummation of marriage (Caldwell, 2015).

Reconstruction of Bridal Attire in Antiquity

In order to reconstruct the bridal attire in antiquity, it is also crucial to examine the artistic descriptions, such as Athenian vase paintings and Roman wall paintings. At the same time, cross-referencing with the literary source is an inseparable process when determining the context of the scenes and the identities of the characters in iconography evidence.

Ancient Greece

Veil

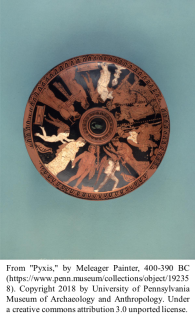

One of the most significant pieces of the bridal outfit in ancient Greece was the veil. The wedding veil can be seen in iconographic evidence such as the vase paintings from the classical era. For example, on this pyxis from Attica (as shown on the right), Eros can be seen adjusting the veil on the bride’s head (Sutton, 1997). She is also depicted being adored in jewelry such as earrings and bracelets. This particular image of a veiled bride is consistent with how Hesoid presented Pandora in his literary work, Theogony. The wedding veil could also be embellished using different patterns.

On this piece of red-figure Ioutrophos fragment (as shown on the left), the bride is covered in a veil that is decorated with a star pattern. Nevertheless, the bridal veil in ancient Greece was not entirely transparent because its function was to hide the brides’ faces from the public view (Llewellyn-Jones, 2003). The veil could be made using a variety of different materials as well, such as linen, fine wool, or silk (Llewellyn-Jones, 2003). There are no surviving Greek texts which directly indicates the color of the wedding veil, thus, it is an incredibly difficult task to determine the exact shade. The Greek word, krokos, often interpreted by scholars as the color, “saffron” or “yellow”, is used in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon to depict the bridal outfit of Iphigenia (238-247). Thus, there is a possibility that the hue of the bridal veil came in a shade of red. However, it would be equivalent to a range of colors consisting of yellow, red, and purple today since the ancient definition on red embodies all of these above colors. Red was a highly symbolic color in ancient Greece, especially in the wedding context, as it represented the social transition in one’s life and status, ripeness and fertility, and the sexual desirability of the bride (Llewellyn-Jones, 2003). The color perhaps also alludes to the bride’s menstrual cycle or first sexual intercourse on her wedding day (Llewellyn-Jones, 2003; as cited in Reeder, 127).

Stephane and Nymphid

Brides from ancient Greece would have also worn a special crown, named stephane on their wedding day. The crown would have been made using different materials. Vase paintings suggest that the crowns were made of metal. Hesoid perhaps also alluded to this tradition when he describes that Pandora was given a gold headband. Ancient authors also indicate that the crowns could also be made of different greenery such as myrtle, poppy, thyme, and flowers (Mason, 2006). For instance, Plutarch suggested in Moralia that “in Boeotia, after veiling the bride, they put on her head a chaplet of asparagus” (Plut. Mor. 2.138.7). The author also stated that the use of asparagus symbolizes the importance of companionship between husband and wife despite the hardships at the beginning of the marriage.

On the same vase painting, Eros, as indicated by his wings, is depicted crouching down at the feet of the bride. This is connected to the practice of brides wearing a pair of special shoes for their wedding day, called nymphid (Oakley and Sinos, 1930). Rest of her attire such as the veil on the back of her head and the jewelry she is wearing is also consistent according to literary descriptions.

Ancient Rome

Veil.

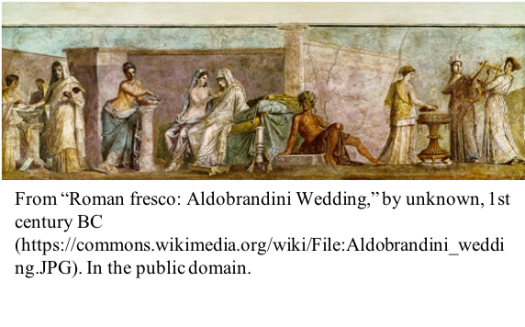

As seen from the literary example of Catullus’s Epithalamium on Vinia and Manlius, not only did Greek brides wear veils on their wedding days, but the Roman brides did the same as well. Iconographic evidence such as frescos provides an artistic depiction of the Roman bridal veil (Olsen, 2008). An important advantage that these wall paintings have is that they provide an idea of the colors that were possibly used for the bridal attire. For example, from the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, one particular set of fresco contains a female figure that was believed to a bride. The betrothal ring on her hand and the marriage contract, as suggested by Brendel, associate her identity as the bride (as cited in Olsen, 2008). The particular yellow-colored veil that she is wearing is also trimmed in purple on the edge. Another example that perhaps depict a bridal scene is the Aldobrandini wedding wall painting (as shown below). This painting has many different readings and its exact meaning remains disputed among scholars today (Olsen, 2008). D’Ambra states that the central figure is the bride and the half-dressed figure who is seen to be comforting her is the goddess Venus (2007). She also suggests that the deep yellow fabric that is folded and placed on the bed right beside the two women is the veil of the bride (D’Ambra, 2007). Furthermore, the bride appears to be wearing a special pair of shoes in an orange-red shade, which is consistent with the depiction given by Catullus in Epithalamium on Vinia and Manliu.

Tunic Recta and Nodus Herculaneum

However, given that brides are covered by their veils, it is not possible to verify the practice of tunica recta and nodus herculaneum. As suggest by Pliny, Roman brides wore a special tunic on their wedding day. Wilson believed that that differentiates a regular tunic and the bridal tunic is that regular tunic would be woven in two pieces, but tunica recta was only woven in one single piece and in general it did not differ from a regular tunic (1938).

Tunic recta would have also been tied using a special belt, ornamented with a knot, known as nodus Herculaneus, or the Heracles knot in English, which symbolizes both chastity and fertility. This knot would then also be untied by the groom (Hersch, 2014; Olson, 2008). Since the veil would have also covered nodus herculaneum, it is impossible to determine its practice from artistic depiction. Since the mythical hero, Heracles, fathered many children, the knot could represent the hope for future procreation. It could also be interpreted as a binding of the bride’s sexuality to her husband (Olson, 2008).

References

Achilles Tatius. (1969). Achilles Tatius. S. Gaselee (Trans.). E. H. Warmington (Ed.). Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press.

Aldobrandini wedding. (2018). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aldobrandini_wedding

Aeschylus. (1926). Agamemnon. In H. Lloyd-Jones (Ed.), Agamemnon libation-bearers eumenides fragments (Vol. 2). (H. W. Smyth & H. Lloyd-Jones, Trans.). Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press.

Caldwell, L. (2015). Roman girlhood and the fashioning of femininity.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Catullus. (1894). The Carmina of Caius Valerius Catullus. R. F. Burton (Trans.). London, UK:R.F. Burton and L.C. Smithers.

D’Ambra, E. (2007) Roman Women. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fantham, E., Foley, H. P., Kampen, N. B., Pomeroy, S. B., & Shapiro, H. A. (1994). Women in the classical world. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

F.C. Babbitt. (Trans.) (1972). Introduction. Moralia (Vol. 4). London, England: Harvard University Press.

Hadas, M. (1952). A history of Latin literature. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Hesiodus. (2005). In The Brill’s New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World (Vol. 6, pp. 279-284). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijike Brill.

Hesiod. (2006). Theogony. In G. W. Most (Ed. & Trans.), Theogony works and days testimonia (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press.

Hesiod. (2006). Works and Days. In G. W. Most (Ed. & Trans.), Theogony works and days testimonia (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press.

Hersch, K. (2014). Introduction to the Roman wedding: Two case studies. The Classical Journal,109(2), 223-232.

Jackie and Bob Dunn. (2018). Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii. May 2006. Room 5, north-west corner. Detail from wall painting of Dionysian mystery. Retrieved from https://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/index.htm

Juno. (2003). In The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Llewellyn-Jones, L. (2003). Aphrodite’s tortoise: The veiled women of ancient Greece. Swansea, UK: The Classical Press of Wales.

Mason, C. (2006). The nuptial ceremony of ancient Greece and the articulation of male control through ritual.Classics Honors Projects. Paper 5.

Oakly, J. H., & Sinos, R. H. (1993). The Wedding in Ancient Athens. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Olson, K. (2008). Dress and the Roman woman: Self-presentation and society. London, UK: Routledge.

Plinius. (2007). In The Brill’s New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World Vol. 11. pp. 383-390). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijike Brill.

Pliny. (1940). Natural History. H. Rackham (Trans.). (Vol 3). Cambridge, MS: William Heinemann.

Plutarch. (1971). Moralia. F.C. Babbitt (Trans.). (Vol. 2). London, England: Harvard University Press.

Plutarch. (1972). Roman Questions. In F.C. Babbitt (Trans.), E. H. Warmington (Ed.), Moralia (Vol. 4). London, England: Harvard University Press.

Sutton, R. (1997). Nuptial Eros: The visual discourse of marriage in classical Athens. The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery,55/56, 27-48.

The British Museum. (2017). Ioutrophos. Retrieved from http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=421988&partId=1&searchText=Attic+red-figure+loutrophoros&page=1

The Creation of Pandora. (2018). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandora#/media/File:J.D.Batten_Pandora_1913.

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. (2018). Pyxis. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/192358.

Wilson, L. M (1938). The Clothing of the Ancient Romans. D. M. Robinson (Ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press.