Contents

- Introduction

- Early Life

- Calydonian Boar Hunt

- “Atalanta in Calydon” by A.C. Swinburne

- Funeral Games of Pelias

- Footrace

- Later Life

- A Parallel of Artemis?

- Gender Ambiguity

- How Does Greek Myth Treat Ambiguous Women?

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources

- References

*Please note this article contains nudity*

1: Introduction

Atalanta is a character in Greek mythology who is best known for her role as a huntress and reluctance to marry. She is often compared to the goddess Artemis, with whom she shares many key traits. Atalanta is depicted in three main myths: the Calydonian boar hunt, the funeral games of Pelias, and the footrace for her hand in marriage. There are discrepancies in our sources regarding where Atalanta is from, some suggest she was born in Arcadia (Apollodorus, 1954; Swinburne, 1896; Apollonius, 2008), others Boeotia (Ovid, 1984). She is said to have married Melanion or Hippomenes, and to have given birth to a son named Parthenopaeus, either by Melanion or the god Ares (Apollodorus, 1954). Ultimately, Atalanta is an interesting figure, as she frequently blends Greek gender distinctions.

2: Early Life

Atalanta is either referred to as the daughter of Iasus (Apollodorus, 1954; Swinburne, 1896) or the daughter of Schoeneus (Apollodorus, 1954; Ovid, 1984). When she was born, her father exposed her to the wilderness because he wanted male children (Apollodorus, 1954). As a result of this, Atalanta grew up in the wild, suckled by a she-bear to remain alive (Apollodorus, 1954), and later rescued by hunters (Apollodorus, 1954).

“Atalanta was exposed by her father, because he desired male children; and a she-bear came often and gave her suck…” (Apollodorus, 1954, p. 399).

The narrative of animal-parented children is not uncommon in Greco-Roman myths, as there are 26 instances of this (Carroll 69). However, Atalanta is one of two females to which this narrative has been attributed to (Carroll 70). This is significant as it places Atalanta within a primarily male tradition.

3: Calydonian Boar Hunt

In this myth, Artemis sends down a boar to terrorize Calydon as punishment for King Oeneus. The king’s son Mealager assembles “all the noblest men of Greece”, along with Atalanta, to hunt the boar (Apollodorus, 1954, p. 67). Meleager kills the boar, however it is Atalanta who lands the first strike on the animal (Apollodorus, 1954). He gifts the boar’s skin to Atalanta as a prize, which greatly angers his maternal uncles, who take the skin from her (Apollodorus, 1954). This causes Meleager to murder his uncles, and in turn is killed by his mother, Althea (Apollodorus, 1954). In some accounts of this myth Meleager is motivated by love for Atalanta in his actions, but in others that motive is not present.

This myth portrays her as talented in her hunting abilities, as she is the first to strike the boar after many failed attempts. It also places her squarely among men, as the only female present. Hunting was viewed in ancient Greek society as an initiation rite for young men, a way for them to transition into adulthood. In this myth, “the initiatory hunt is perverted”, as Meleager’s life ends in disaster, murdered by his own mother (Barringer, 1996, p. 61). This could represent how a woman’s role in traditionally male realms, such as hunting, is a perversion of gender distinctions and causes tragedy. Regardless, the Calydonian boar hunt displays Atalanta as a figure of skill and rare female independence.

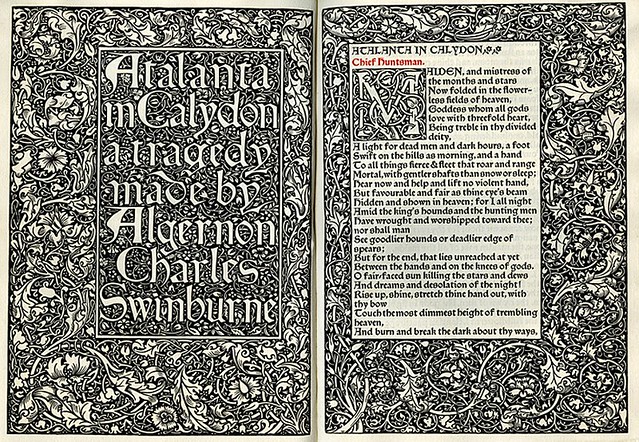

4: “Atalanta in Calydon” by A.C. Swinburne

This tragedy, written in 1896, was influential in bringing attention to the character of Atalanta in more recent years. The play centers around the Calydonian boar hunt and Meleager’s demise as a result of his love for Atalanta. Swinburne further romanticizes this myth, asserting that Meleager gives the boar’s skin to Atalanta because he was enamored with her (Swinburne, 1896). In this way, he shapes the modern conception of Atalanta as a figure of romance. This contends with her characterization in Greek myth as one who sets herself apart from romantic tendencies.

5: Funeral Games of Pelias

In this story, Atalanta is victorious in a wrestling match against Peleus at the funeral games of Pelias (Apollodorus, 1954). There is limited literary evidence for this myth, as Atalanta’s attendance is only mentioned in passing by Apollodorus and Hyginus (Barringer, 1996, p. 67). This scarcity is supplemented by iconographic evidence from black-figured vases, such as the one depicted below (Barringer, 1996). This myth is significant as Atalanta is undertaking what was perceived as an exclusively male activity, strengthening her ambiguity as a character with both feminine and masculine traits.

6: Footrace

The third myth of Atalanta is the footrace, where she agrees to marry the suitor who beats her in a race. In many of these accounts, the race is instigated by Atalanta herself as an attempt to evade marriage, “I am not to be won… till I be conquered first in speed” (Ovid, 1984, p. 105). Atalanta is often armed and chases behind her suitor trying to catch him. The result of this is that she is again portrayed as the hunter, not the hunted. Apollodorus records that Melanion was her suitor, while Ovid asserts it is Hippomenes. In Ovid’s account, Aphrodite tosses three golden apples into the path of Atalanta, slowing her down and allowing Hippomenes to win (Ovid, 1984).

In this myth Atalanta competes for herself, independent of a male representative. However, this degree of independence is still limited as Atalanta is eventually forced to marry. Despite her efforts, she remains susceptible to the limits of females in antiquity. This myth incorporates many central themes of Atalanta’s myths: hunting, initiation into adulthood and Atalanta in the masculine role as hunter.

7: Later Life

The late life of Atalanta is one of punishment and disaster. According to Ovid, Atalanta and Hippomenes were punished by Aphrodite for not thanking her for her help in their marriage (Ovid, 1984). Aphrodite forces the couple to consummate in a temple of the goddess Cybele, who turns them into lions as punishment (Ovid, 1984). In Apollodorus’ account, Atalanta and Melanion entered the precinct of Zeus to have sexual relations while they were hunting, which causes Zeus to turn them into lions (Apollodorus, 1954).

The fact that she was transformed into a lion is significant, as lions were believed by ancients not to have sex with each other or at all (Barringer, 1996). In this way, there is a degree of punishment for Atalanta being sexually active and for not conforming to gender distinctions. Ultimately, Atalanta must return to her life in the wild, suggesting that it is not possible for her to exist as an ambiguous figure in Greek society.

8: A Parallel of Artemis?

Attribution: Eric Gaba, Wikimedia Commons user Sting)

Many traits of Atalanta are in parallel to the goddess Artemis, so much so that Atalanta is sometimes perceived as a form of the goddess herself. Most significantly, both women fit into the archetype of “virgin huntresses” and are often described as “swift-footed” or “footed as the wind” (Swinburne, 1896, p. 2). They are also alike in their role as archers and as maidens who oppose marriage. Overall, they represent the danger and ambiguity of transitions for women in antiquity, both expressing an intense desire to remain liminal.

Atalanta is entangled with Artemis throughout her mythological life. She is said to have hunted in the wilds with the goddess, denoting some type of personal relationship between the two women (Barringer, 1996). She is again involved with her in the Calydonian boar hunt, as it is Artemis who sends the boar to Calydon as punishment to King Oeneus. In Swinburne’s tragedy, Artemis lets Atalanta slay the boar because of her affection towards her (1896). Furthermore, she returns to the wild with Artemis when she becomes a lion, “sentenced to hunt forever” (Barringer, 1996, p. 76). Atalanta’s relation to Artemis is a significant aspect of her role in Greek myth and how she has been perceived throughout history.

9: Gender Ambiguity

The most significant aspect of Atlanta’s character is her ambiguity, and the way in which she challenges Greek notions of gender. She frequently engages in masculine discourses such as: hunting, wrestling, racing and wearing armour (Barringer, 1996, p. 49). Additionally, Atalanta’s interaction with Jason as “eager to follow on his voyage”, shows a woman who is attempting to perform the activities of a heroic male (Apollonius, 2008, p. 65). In these ways, she is more closely linked to maleness than femaleness. Despite her masculinity, Atalanta’s femininity ultimately wins out as she is forced to confine to the institution of marriage. She is also prevented from joining the voyage of the Argonauts for fear of “bitter rivalries provoked by love” (Apollonius, 2008, p. 65). Despite her exceptional abilities, she is limited by her femininity.

Through Atalanta’s blending of female and male attributes she suggests the possibility that gender is not as separate as it is often portrayed. She is a complex character, as she poses a threat to male order, but is also the subject of male desire (Barringer, 1996). This tension offers insights into gender dynamics in Ancient Greek society and how her presence challenges these dynamics.

10: How Does Greek Myth Treat Ambiguous Women?

The notion that a woman should be passive and under the control of men is “expressed in virtually every Greek myth” (Lefkowitz 207). However, there are some instances of mythological women, similar to Atalanta, who challenge this norm.

Atalanta can be compared to another group of women who appear in the story of the Argonauts, the Lemnians. These women were also cursed by Aphrodite, causing them to have a repulsive smell (Apollodorus, 1954). After their husbands decide to take up with slaves from Thrace, the Lemnian women murder the males on the island (Apollodorus, 1954). When the Argonauts arrive, the Lemnians are in severe emotional distress at the crimes they have committed (George 62). Similar to Atalanta, these women are viewed as independent and are portrayed as hunters through the murder of the Lemnian men (George 60).

“Thus dishonored, the Lemnian women murdered their fathers and husbands…” (Apollodorus, 1954, p.99).

Another comparison can be made to the Amazonian women, who were skilled archers and rejected the institution of marriage (Walcot 42). The Amazons are portrayed as “everything a woman ought not to be” because of their rejection of gender norms. Ultimately, they demonstrate the consequences of women not confining to the norm and express male fear at this possibility (Walcot 42).

The Amazons were “a people great in war; for they cultivated the manly virtues” (Apollodorus, 1954, p. 203).

Greek myth tends to present ambiguous women as dangerous to the livelihood of men, as most of these stories end in disaster. While Atalanta’s role in myth is extremely rare, it is not an anomaly. She fits into this tradition of nonconforming women in Greek myth being treated as a problem, thus exposing basic fears and anxieties that men in antiquity felt towards women (Walcot 39).

11: Conclusion

Atalanta is an extremely impactful character in Greek myth for her role as a woman of ambiguity. These myths have provided rich material for writers and artists throughout history, as displayed throughout this article. She is a valuable character to examine because she represents an exception, who is set apart from many other mythological women. The ideals she represents and social constructs she challenges in her actions, are significant as they are extremely different from accepted Greek constructs. Through Atalanta, one can examine the blending of many significant relationships in Ancient Greece; male and female, mature and immature, insider and outsider. Thus, making her one of the most interesting and complex depictions of a woman from antiquity.

12: Additional Resources

http://www.theoi.com/Heroine/Atalanta.html

https://www.greek-gods.org/greek-heroes/atalanta.php

https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/heroine-atalanta/

13: References

Apollodorus. (1954). The Library I. (J. G. Frazer, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Apollonius Rhodius. (2008). Argonautica. (W. H. Race, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barringer, J. M. (1996). Atalanta as Model: The Hunter and the Hunted. Classical Antiquity, 15 (1), pp. 48-76.

Carroll, M. (1984). The Folkloric Origins of Modern “Animal-Parented Children” Stories. Journal of Folklore Research, 21(1), 63-85.

George, E. (1972). Poet and Characters in Apollonius Rhodius’ Lemnian Episode. Hermes, 100(1), 47-63.

Lefkowitz, M. (1985). Women in Greek Myth. The American Scholar, 54(2), 207-219.

Ovid. (1984). Metamorphoses II. (F. J. Miller, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Swinburne, A. C. (1896). Atalanta in Calydon: A Tragedy. London, ENG: Chatto & Windus.

Walcot, P. (1984). Greek Attitudes towards Women: The Mythological Evidence. Greece & Rome, 31(1), 37-47.