Mythology

You may have heard of Oedipus, the mythological figure who gave his name to the Oedipus Complex, the Freudian condition in which a man is said to be naturally inclined to be sexually attracted to his mother and resentful towards his father. During the 5th century BCE, readers were introduced to a written version of the myth of Antigone, a daughter of Oedipus. Recorded earliest by Sophocles in c. 441 BCE, and Euripides in c. 420-206 BCE, Antigone has endured two millennia to the modern day. The story’s significance largely originates from the uncommon depiction of a female protagonist in antiquity who is portrayed as a hero while defying state law. Antigone’s quest to deliver the proper burial rites to her fallen brother Polynices does not align with the socially-acceptable idea of an ancient Greek woman; rather, when viewing Antigone’s actions in the context of Ancient Greece, they are far more radical and conventionally masculine compared with how a reader with a modern bias might view them. Antigone’s defiance of the Theban king Creon may have simply been an act of familial love, but it has been adapted into many modern creations as a symbol of an individual act of rebellion spiralling into a large-scale revolution. (Sophocles, 2008.)

Social Politics

“There is no happiness where there is no wisdom;

No wisdom but in submission to the gods.”

Following the deaths of her father Oedipus and brothers Polynices and Eteocles, Antigone is placed under the care of her uncle, Creon… who happens to be the king of Thebes. However, she disobeys her kyrios when he refuses to allow her to bury Polynices, who is viewed as a traitor of the state for attempting to seize the Theban throne. Antigone is portrayed as a stubborn woman, who is willing to go so far as to defy her male guardian (who is also her ruler), and defy state law.

On the surface, Antigone is presented as a respectable, dutiful Greek woman. She is introduced as being happily engaged to her cousin, Haemon—she is fulfilling the duty of the female citizen by marrying, and reproducing more Greek citizens. Before Oedipus dies in Oedipus at Colonnus, Antigone appears as a minor character in order to lead her blind father into exile, staying solely in the context of familial duty. As she becomes the central protagonist of Sophocles’ Antigone, she comes into her own as a hero-type figure who is determined to uphold the will of the gods and help her brother enter the afterlife. (Sophocles, 2008.)

Around the writing of Antigone, Sophocles was serving the military as a general leading an expedition against Samos. Despite this, Antigone does not particularly use propaganda to make definite arguments for or against the sides of Antigone and Creon. Both characters are shown to be both right and wrong, and there is care shown to avoid trapping the story in the ancient Athenian setting. Creon is a leader who is given little other choice than to uphold his sovereignty or risk weakening it; Antigone is a young female citizen who acts rashly and lashes out at her sister for trying to save her. Nevertheless, the story has been seized by modern writers as a symbol of righteous rebellion. (Collard & Cropp, 2008.)

Antigone and the Hero

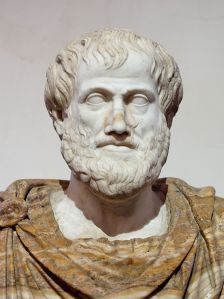

In Aristotle’s Poetics, he offers a specific outline of traits possessed by the tragic hero. We see that the Aristotelian hero is one who acts on their morals positively: Aristotle states that “the character will be good if the purpose is good. … Even a woman may be good.” (Aristotle, 2008, Section 2, Part XIV.) He then lays out the structure of a hero’s story: the hero is rich and/or powerful, but possesses a hamartia (tragic flaw or error) that leads to his downfall, and hubris (pride). The hero then experiences peripeteia (a reversal of fortune), and finally suffers nemesis (a severe punishment). Antigone’s father Oedipus is known to be one of the greatest examples of a tragic hero, as he embodies each of these qualities in a story that becomes increasingly violent and full of poor beliefs and decisions. In Antigone, it is often argued by scholars that Creon is actually the true tragic hero of the story, but Antigone herself is able to fulfill this role. By violating the law and choosing to follow her personal agenda, Antigone’s hamartia—this hubristic belief that she is morally superior, regardless of the consequences—leads her straight into her reversal of fortune by imprisonment, and concludes the story in the tragic final chapter where several characters commit suicide. (Aristotle, 2008.)

Gender Politics

“… weak women, think of that,

Not framed by nature to contend with men.“

The gender politics of Antigone are best examined through the interactions and differences between the two main female characters of Antigone and Ismene. Antigone’s sister Ismene is viewed as the more conventional Greek woman. She does not wish to draw attention to herself or be spoken about, like the concept of a virtuous woman. She stays in the context of the home over the course of the play, and displays her devotion to family by attempting to persuade Antigone to abandon her quest to save her from being executed. Ismene’s devotion also causes her to return to Thebes with Antigone, and later request to be executed along with Antigone when the latter is sentenced to death for her treasonous activities. Ismene is last mentioned in Antigone being pardoned by Creon and saved from death, while her titular sister is imprisoned in a cave and commits suicide. The endings for these two women—the devoted, feminine Ismene and the obstinate, masculine Antigone—are vastly different and seem to carry a connotation of punishment for straying outside of the established gender roles.

Ismene appears to uphold the judicial law by refusing to aid Antigone in carrying out the burial rites; where Antigone is determined to adhere to divine law even at the risk of death, Ismene’s fear of punishment overcomes her desire to protect her family—in not helping administer burial rites to their brother’s body, Ismene would be refusing him entry to the afterlife and condemning him to an eternity of suffering. Greek women were associated more commonly with funerals and the dead than men were; this supports the idea that Ismene ultimately chooses the side of judicial law by refusing to perform an essential duty for a woman, despite serving as the play’s embodiment of femininity. (Sophocles, 2008.)

It is important to note that the modern adaptations of Antigone examined below all similarly portray Antigone as a revolutionary who was not inherently a political figure, but rather an ordinary citizen rising up against an oppressive government. Antigone acts only when her family is threatened, keeping in line with the concept of the proper Greek woman. This, alongside Ismene’s defending of judicial law above natural law, is one of the very few instances in which Antigone and Ismene appear to trade roles. It is also significant that the fragments of Euripides’ Antigone contain a different ending for Antigone, where she marries Haemon—who had helped her to bury Polynices in this version—and then has a child, Maeon, with him. This version appears to be more socially-acceptable for the time, as Antigone is not a woman acting independently. The inclusion of Haemon hands the responsibility over to him, and allows Antigone to ultimately survive and experience a happy ending. (Collard & Cropp, 2008.)

Antigone in Media

Below are five examples of contemporary adaptations of Antigone. This list is not exhaustive; since at least 1839, Antigone has been adapted into numerous varied cultures and languages. It has been adapted into Modern Greek, German, Welsh, Modern English, Papiamento, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Farsi, Syrian Arabic, and more. Antigone has been adapted into various forms of media including film, television, radio, stage theatre, musical theatre, dance, opera, photography, sculpture, painting, musical compositions, and text. This list will show you how versatile Antigone’s story is, and hopefully inspire you to seek out more adaptations… and perhaps even create your own.

Antigone by Jean Anouilh, 1944

French-language play written during the Nazi occupation of Paris, only months before the city’s liberation in August 1944. The original characters are depicted, though there are parallels drawn between Antigone and members of the French Resistance, and Creon and Philippe Pétain of the Vichy government. The play was heavily subjected to Nazi censorship, though its author was a fairly apolitical figure… a fact that likely helped the play get approved by the government. (Smith, 1985.) Here, Antigone’s desire to bury her brother is derived not from a sense of duty to the deceased, but rather as a defense of the concept of freedom itself. (Anouilh, 1944.) Français (PDF), English (PDF)

Antigòn an Kreyòl by Félix Morisseau-Leroy, 1953

Haitian Creole-language play that recontextualizes Antigone as a Haitian Vodou goddess. The play draws on a colonialist conflict originating from the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804 against the French colonial empire. Haiti, which had been under French colonial rule since 1534, began to see a resurgence of Vodou culture after the United States occupation of Haiti ended in 1934. (Fradinger, 2011.) Rather than alluding to the Greek gods, the play utilizes the Haitian pantheon of loa (spirits). In this play, two cultures battle: the minority Vodou practicers and speakers of Haitian Creole, and the majority French-speaking Catholic elite. (Morisseau-Leroy, 1953.) English

La Pasión según Antígona Pérez by Luis Rafael Sánchez, 1968

Spanish-language play which portrays Creon as a Latin American dictator, with Antigone and Polynices as dissident freedom fighters. This adaptation gives Antígona a different priority, as she wishes to be free of the political tension in her homeland; instead of burying a brother, she buries two friends. The familial themes of the original work are dissolved here: Ismene is a friend of Antígona’s, and Haemon is simply an officer of Generalísimo Créon Molina’s army. (Sánchez, 1968.) Antígona is also uniquely portrayed as committing terrorist actions and conspiring to assassinate Créon; this sets her apart from Antigone, whose actions as a devoted sister did not inherently mark her as being on the wrong side of the law and thus allowed for a more objective characterization. Of the works examined, Sánchez’s takes the most significant departure from the original material. (Fiet, 1976.) Español (PDF), English

“Rabeya (The Sister)” dir. Tanvir Mokammel, 2008

Bengali-language film that depicts Antigone and Ismene as two sisters named Rabeya and Rokeya during the 1971 Bangladeshi Liberation War. Polynices is portrayed as a Bangladeshi guerrilla who has been denied his burial rites, and Creon as a wealthy local Muslim League leader who sides with the attacking Pakistani army. Rabeya (Antigone) is shot and killed when she tries to bury Khaled’s (Polynices) body; she is not killed by herself or Creon, but the blame for her death still lies with the institution of war and the instigators of war—namely, political figures like Creon. The pro-resistance message is much more explicit in this adaptation, as Rabeya is hailed as a martyr and the guerrillas achieve victory. (Mokammel, 2008.) বাংলা (English subs) [YouTube]

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie, 2017

English-language novel depicting Antigone and Ismene as Muslim women in the modern Western world under the shadow of ISIS/ISIL, with Polynices as a naïve boy drawn to the nationalistic propaganda of ISIL. The influence of Sophocles is strongest when Aneeka (Antigone) is furious with Isma (Ismene) for telling the authorities about Parvaiz (Polynices) fleeing to work for ISIS. Betraying the family, and therefore natural law, is more inexcusable than joining a radicalist organization and violating judicial law. Eteocles does not exist in many adaptations, but his absence is felt strongly here because it further pushes the idea that natural and divine law both supersede judicial law by removing the storyline of fratricide. (Shamsie, 2017.) English [Amazon]

References

Anouilh, J. (1944). Antigone. London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

Aristotle (2008). Poetics (S. H. Butcher, Trans.). Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1974/1974-h/1974-h.htm

Collard, C.; Cropp, M., eds. (2008). Euripides Fragments: Aegeus–Meleager. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Deutsch, R. (1946). Anouilh’s Antigone. The Classical Journal,42(1), 14-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3292337

Fiet, L. (1976). The Passion of Antígona Pérez: Puerto Rican Drama in North American Performance. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/148646803.pdf

Fradinger, M. (2011). Danbala’s Daughter: Félix Morisseau-Leroy’s Antigòn an Kreyòl. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277666068_Danbala’s_Daughter_Felix_Morisseau-Leroy’s_Antigon_an_Kreyol

Mokammel, T. (Producer). (2008). Rabeya (The Sister) [Motion Picture]. Bangladesh: Kino-Eye Films.

Morriseau-Leroy, F. (1953). Antigòn an Kreyòl. Paris: Présence africaine.

Sánchez, L. (1968). La Pasión según Antigona Pérez. Retrieved from http://smjegupr.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/La-pasi%C3%B3n-seg%C3%BAn-Ant%C3%ADgona-P%C3%A9rez.pdf

Shamsie, K. (2017). Home Fire. New York City, NY: Riverhead Books.

Smith, C. (1985). Jean Anouilh, Life, Work, and Criticism. London: York Press.

Sophocles. (2008). Antigone (R. C. Jebb, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: BiblioBazaar.

Reblogged this on Personal Musings:.

LikeLike