The marriage ceremony in Ancient Greece did not have the same implications as it does today. It was not in any way a legal ceremony, due to the fact that there was no ancient equivalent of a marriage certificate. Instead, it was considered a successful and binding marriage simply through the fact that family members bore witness to the event (Robson 2013). Marriage was not simply about benefiting the couple, but Greek society as a whole. A union of two powerful oikos (households) would greatly benefit both families, and would be a showcase of strength to their community (Robson 2013).

This fact can be seen in images of wedding processions from ancient Greece. In many classic images, the groom holds the wrist of his new bride, signaling his possession of her and showing his dominance over her (MFA loutrophoros).

According to the Greeks, marrying off girls when they are still young is in the best interest of the bride. The main cause of physical maladies in women was perceived to be “hysteria”, also known as a wandering womb. The cure was to marry her, quickly, and to get her pregnant right away. The baby would put weight on the womb to hold it in place, and keep it from traveling throughout the body, where it might choke her, or affect her heart and brain (McClure 2020).

There is a distortion between the real life of ancient Greeks and the way they chose to portray themselves. In images, whether on pottery or through art or some other medium, brides are seen to be much older than they really were, to the point where they were depicted as around the same age as the grooms.

In one classic image of a lekythos, a vase that stores oil, the bride’s breasts are emphasized, and the couple gaze at each other in a way that implies the consummation of their marriage is near, emphasizing their mutual maturity (Pergamon lekythos).

The wedding ceremony itself was typically a three day event. The preparation day was known as the proaulia, the ceremony itself was known as the gamos, and the day after was known as the epaulia (Mason 2006). While this might have been the norm, it was not an absolute, and there would almost certainly be variations of this process (Mason 2006).

Proaulia

The day of preparation was reserved for several important activities to be undertaken by the bride and groom. Sacrifices, dedications, and the pais amphitales tradition were all performed on this day, and other family members may have engaged in some ritualistic activities as well (Mason 2006). Sacrifices were extremely important, as the ancient Greeks wanted to make sure the gods and goddesses were appeased and would protect the couple. Young girls would often make sacrifices to Artemis, who was their protector up until marriage age. Sacrifices to Artemis were seen as appeasing her, and thanking her for her protection (Mason 2006). Sacrifices would also be made to Aphrodite, because married, adult women fell under her domain (Dillon 1999).

Dedications were performed to Artemis by the bride to be. The main purposes for these were to thank Artemis for her protection so far, and to ensure her protection during childbirth (Mason 2006). Often, these dedications would take the form of cutting off the bride’s “maiden’s hair” (Dillon 1999). In Sparta, the bride’s hair was militaristically shaved close to the skull (McClure 2020). In some parts of Greece, such as Megara or Delos, girls dedicated their locks of hair to virgin heroes (Mason 2006). A girl’s virginal girdle was also removed and dedicated to deities. She had worn it since the onset of puberty. This marked another example of a bride transitioning to become a woman (Dillon 1999). Occasionally, the girdle was dedicated before childbirth to pray for a successful delivery (Dillon 1999).

The tradition including the pais amphitales occurs the night before the ceremony. A small boy, with two living parents, would sleep with the bride in the groom’s house (Mason 2006). This tradition showcases the fact that a wife’s main purpose is to produce children, especially male heirs (Mason 2006).

Gamos

The morning of the wedding, the bride took a symbolic and ritualistic bath. It was such an important part of the wedding process, that even if a girl had died before marriage, her family would ensure her body was still bathed (Mason 2006). This was a ritual, it appears to be, reserved for the bride–the groom either did not bathe, or it was not as important as hers. The groom has already gone through coming of age ceremonies, but the wedding is the real transition from girlhood to womanhood for the bride (Mason 2006). A specific water holder, known as the loutrophoros, was used for important events such as weddings (Mason 2006). The water held in the loutrophoros had to come from a particular source, depending on where the wedding is taking place. It was thought that the source of the water would aid the couple in fertility (Mason 2006).

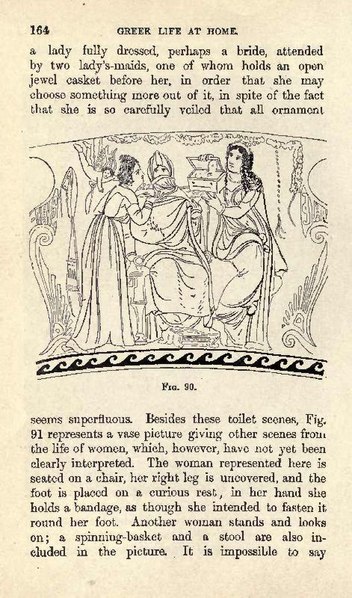

After the ritual bath, the bride was dressed for the wedding with the help of the wedding attendant known as a nymphokomos, because it was not easy to dress the bride (McClure 2020). This was an opportunity for wealthy families to show off, due to the fact that the bride was dressed as ornately as possible. The bride’s veil was often depicted being made from saffron, most likely because saffron was used to cure illnesses that arose from menstruation (Mason 2006). She would wear a necklace and a crown known as a stephane (Mason 2006). Various regions and primary sources describe the stephane being made out of different materials.

Vase paintings usually indicate it was made from metal, but Plutarch describes them being made from asparagus,

“For this plant yields the finest flavoured fruit from the roughest thorns, and so the bride will provide for him who does not run away or feel annoyed at her first display of peevishness and unpleasantness a docile and sweet life together”

-Plutarch, Moralia 138 D

The groom would also have been adorned, and although sources mostly focus on the bride, grooms were known to wear an intricately ornate cloak and a garland on top of his head.

The feast would have occurred next, either at the bride or groom’s house (Mason 2006). Both men and women would have eaten together at the same table, although on separate sides, which was uncommon (Robson 2013). The general atmosphere of this event was loud and merry, in no doubt aided by the food, wine, and eventual dancing (Robson 2013). Distinctive wedding songs, known as hymen hymenaios, were sung by the guests frequently (Mason 2006). The unveiling of the bride was known as the anakalypterion (Mason 2006). Some experts believe that it could have occurred upon arrival at the groom’s home later that evening, or the morning after the consummation, or during the giving of gifts. It is also possible that there could have been several unveilings (Mason 2006). Because Ancient Greek vase painting are dramaticized and often idealized, it is difficult to dissect which scenarios were more accurate than the others.

The next stage of the ceremony was called the wedding procession or the chariot procession. However, in most cases, it was unlikely that a chariot was actually involved. Most likely the “chariot” was either a small cart, or the bride and groom walking on foot to his oikos, her new home (Mason 2006). This was one of the more difficult stages of the wedding for the bride, having to leave her childhood home and family for a new and potentially unfamiliar oikos, where she would have felt like an outsider. This stage was deemed important because anyone who looked outside or heard the revelry would be able to see the union of the bride and groom, therefore marking its legitimacy on society (Mason 2006).

On vase paintings, the wedding procession was very common. The people referenced on the vases usually include the bride and groom, Eros (god of passion and desire), and either the bride’s mother or the groom’s mother. The groom’s mother is usually depicted waiting in the doorway of her oikos, holding two torches, and waiting to welcome her new daughter in law to her home (MFA loutrophoros).

That evening, the bride would have to be accepted in her new home. There were several rituals the family would have to go through, similar to those when a baby is born to an oikos (McClure 2020). For instance, the new bride would be led around the hearth in a similar fashion as as new infant (McClure 2020). The bride would be given a ripe fruit (potentially symbolizing her fertility) and her acceptance of it would be symbolic of her accepting her role in producing children (Mason 2006). However, other theories have also been brought up. Sutton believed there was a connection between the fruit and Persephone eating the pomegranate from Hades, which would symbolize the fact that it is difficult to be broken from her new oikos (Mason 2006). Plutarch believed that it was to keep the bride happy, because,

“the delight from lips and speech should be harmonious and pleasant at the outset”

-Plutarch, Moralia 138 D

Another ritual that the bride and groom would undertake together would be being showered with katachysmata, which were items (believed to be dates, coins, dried fruits, figs, and nuts) that symbolized the fertility and longevity of the new couple (Reeder 1995). It is possible that this event could have occurred either in the groom’s home or outside of it, where guests could take part in the ritual as well (Reeder 1995). The fact that so many rituals with the bride were to wish her well in bearing children at such a young age was well intentioned but could easily have been overwhelming. The simple fact that she was getting married to a man who was most likely twice her age and leaving her friends and family home for an uncertain life would have already been cause for sadness and discomfort from the bride.

In vase paintings, the bride is often depicted as unfeeling. She had been adorned beautifully to signify her wealth, showered with items to signify her fertility, and veiled to signify her status as an object, or property, for her husband. It is possible the veil also served the purpose of warding off evil and misfortune, but it proved effective in silencing her (Mason 2006).

The last ritual of the night would be the consummation of the marriage between the bride and groom. While it would have occurred behind closed doors, there were guests stationed on the other side of the door (Mason 2006). One of the groom’s friends would have been there to guard the hallway, both keeping people out of the room and making sure that the bride or groom did not try to escape (Mason 2006). Other guests (possibly children) would be singing a traditional wedding song called an epithalamium (Epithalamium 2017). Scholars have maintained that the song would have been sung loudly to hide the cries of the bride (McClure 2020). However, the lyrics simply indicate wishing the couple happiness and blessing them (Epithalamium 2017). It is possible that there was one group who would sing into the night and another group who would take over in the morning to awaken the couple (Epithalamium 2017).

Epaulia

The third and final day was known as the epaulia, which was specifically known as the giving of gifts (Robson 2013). The gifts would have had many purposes, from ensuring that she had everything she would need in her new oikos from her family (specifically her father) or welcoming her into her new family from the groom’s side (Mason 2006). She would have given the groom a chlanis, a tunic that she had woven herself (Mason 2006). The third day was also marked by more feasts and dancing. The bride would cook an entire meal for as many male relatives related to her new groom as possible, and would have been an important step for her to be accepted into the oikos and to assure that a legitimate wedding had occurred (Mason 2006). This was referred to as the gamelia (Robson 2013). The groom would have marked this as important to assure that if his wife bore him any sons, he would be enrolled in the phratry (a group with hereditary membership) (McClure 2020). Finally, the bride dedicated a loutrophoros to a nymph in thanks of the marriage and in hopes that she would have a good life ahead of her (Mason 2006). The completion of the wedding ceremony would have solidified the bride’s transition to nymphe, where she will remain until the birth of a child (McClure 2020).

However, different parts of Greece certainly had different customs. In Sparta, girls were at least around age eighteen before they married, because being a healthy mother was of the utmost importance to raising warriors (McClure 2020). Because the groom lived in the barracks with other men, the couple only had brief visits with each other at night for at least the first year of their marriage. During that time, they might not even get to see their partner’s face, considering they consummated their marriage quickly in a dark room with a single bed, before the husband had to leave to join the barracks again (McClure 2020). Athenian wedding ceremonies appear to be positively romantic in comparison, but there would also have been less extreme scenarios in different geographical areas.

Citations

Blümner, Hugo, 1844-1919, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dillon, M. (1999). Post-Nuptial Sacrifices on Kos (Segre, “ED” 178) and Ancient Greek Marriage Rites. Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik,124, 63-80. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20190338

[Lekythos depicting a warrior and a bride]. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany.https://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/XDB/ASP/recordDetails.asp?id={15088787-6775-49CC-9 56C-7665AE70F616}&noResults=1&recordCount=1&databaseID={12FC52A7-0E32-4 A81-9FFA-C8C6CF430677}&search=%20{AND}%20%20[Vase%20Number]%202041 02

[Loutrophoros depicting a wedding procession]. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany.https://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/XDB/ASP/recordDetailsLarge.asp?recordCount=1&id={6 5F737AA-C3B2-4984-8BB8-CDBE32359EDE}&returnPage=&start=

Mason, C. (2006). The Nuptial Ceremony of Ancient Greece and the Articulation of Male Control Through Ritual. Classics Honors Projects. 5. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/5

McClure, L. (2020). Women in classical antiquity: From birth to death. H oboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Plutarch. (138 D). Moralia.

Projects, C. (2017, November 21). 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Epithalamium. Retrieved October 13, 2020, from

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Epithalamium

[Pyxis depicting a bride, groom, and nymphokomos] . Musee du Louvre, Paris, France.https://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/XDB/ASP/recordDetails.asp?id={79BD7F93-E0D9-4A2D -8FD7-74D4CA37764A}&noResults=64&recordCount=27&databaseID={12FC52A7-0 E32-4A81-9FFA-C8C6CF430677}&search=%20{AND}%20Greek%20wedding%20vas es

Reeder, Ellen D., ed. Pandora: Women in Classical Greece. Baltimore, Maryland: Walters Art Gallery, 1995.

Robson, J. (2013). Sexual Unions: Marriage and Domestic Life. In Sex and Sexuality in Classical Athens ( pp. 3-35). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/j.ctvxcrq1q.7

Disclaimer

This site contains copyrighted material made available in an effort to advance understanding of the topic discussed in the article. This constitutes ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit.

2 thoughts on “The Ancient Greek Wedding Ceremony”