Content disclaimer: The following article describes human remains and includes one photo of a human skull. All other photos of skeletal remains are linked and can be viewed at your own discretion.

Human bones make up a very important organ system that responds to internal and external stimuli in a variety of different ways. Disease, nutrition, physical activity and stress are all factors that can cause permanent or temporary changes to different bones in the body (Liston, 2012 pp.125-126). What makes the study of bones so special is that they tell a story – the events that occur during one’s lifetime can create permanent changes to bone which can be studied many years later by scientists and historians.

Forensic archaeology is the study of human remains from the past. Forensic archaeologists analyze skeletal remains that are uncovered from archaeological excavations and conduct experiments to answer basic questions such as…

- Who was this person?

- What was their life like?

- Where were they from?

- When were they alive?

- Why are their bones so important?

During early excavations, archeologists only kept skeletal remains that were large and fully intact, thus discarding smaller, more brittle bones that may have been important (Liston, 2012 pp.126). The majority of the research conducted on ancient bones are on larger bones that survived cremation or long periods of time under ground, such as the long bones and the skull (Liston, 2012 pp.126). Although we are missing a lot of skeletal evidence from the people of the past, the evidence that has survived has allowed us to put together a puzzle with many missing pieces.

The following article will discuss…

- How to determine the sex of bones

- Examples of women from antiquity whose bones have been sexed

- Diseases that can be identified on skeletal remains such as joint diseases and cancer

- Evidence observed on bones due to women’s occupational actives

- Trauma evident on female skeletal remains

Sexing bones

Once the bones are discovered, the next step is sexing them. This means analyzing the bones and comparing them to other bones, as well as using modern day anatomical knowledge to determine the sex of the bones. So, how is this done? It depends on which bones are discovered, how intact they are, how much is missing and how well they are preserved.

There are several ways to differentiate sex based on adult skeletal remains. Female bones are generally smaller, smoother and more delicate compared to male bones (Liston, 2012 pp.128). Female skulls are smaller in comparison to male skulls which are wider and more square than female skulls (Liston, 2012 pp.128).

The pubic bone (pubis) is one of the easiest and best ways to determine the sex of a skeleton (Liston, 2012 pp.128-129; Leong, 2006 pp.61). Females are the only sex able to bear a child, and before a woman is even pregnant her pelvis is more open and broader with wider pubic angles and outwardly flared hip bones (Leong, 2006 pp.61). The increased amount of area surrounding the pelvic region allows the uterus to grow and accommodate for a growing child once conceived (Leong, 2006 pp.64). Additionally, sometimes scarring can be seen on a woman’s pelvic bone due to one or numerous completed childbirths, but this is not the case for every pelvis found (Leong, 2006 pp.64).

Click and slide the arrows up and down to see the differences between the male and female pelvis!

Watch this video to learn more about the process of sexing skeletons (Source; Durham University)

A telling indicator of sex is grave goods that accompany human remains. When ancient cemeteries or gravesites are executed, belongings of the deceased individual are often found buried alongside of them (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.17). There are certain objects that are associated with women’s burials, such as earrings, necklaces and rings and certain objects are associated with men’s burials, such as weapons and tools (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.21). To read more about Ancient Greek funerary practices and grave goods, read this page!

There are many examples of women who were identified using both their bones as well as the grave goods accompanying their remains. In 1980, an excavation took place at the hillock of Toumba at Lefkandi, where cremated remains of a man and a full skeleton of a woman were found at the centre of the building (Kosma, 2012 pp.60). It was suggested that the woman was buried in a wooden coffin along with various burial goods (Kosma, 2012 pp.61). The large amount of jewelry that was found with her body can be an indication of her social status when she was alive, as only a woman of wealth could have afforded such pieces (Kosma, 2012 pp.60). Additionally, two gold discs covered each breast and scholars suggested that these discs were part of Mycenaean tradition (Kosma, 2012 pp.61).

To view the images of her skeleton and the location of her burial click here!

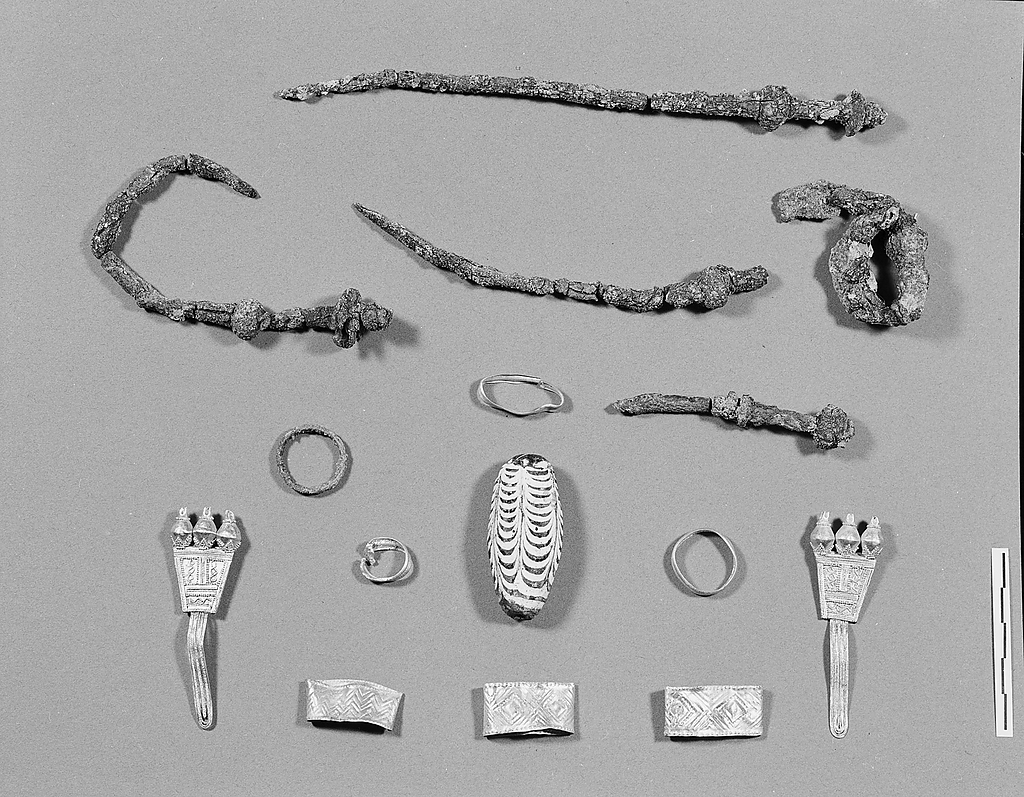

Another example are the cremated remains of a woman called the “Rich Athenian Lady,” which were found during the Agora Excavations in 1967 (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.8). A burial was uncovered that contained a cinerary urn as well as a variety of offerings (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.12). The offerings surrounding the urn were of high value, indicating that the grave was of someone very wealthy (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.29). Furthermore, remains of smaller bones were found that did not belong to an animal (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.15). It was later discovered that these bones were of a fetus, thus establishing that the woman who was buried here was either pregnant or had just given birth (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.15). Throughout the excavation process, almost the entire skeletal system of the lady was recovered and was in good condition (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.16). What was extraordinary about this discovery is the preservation of the facial bones (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.15-16). In most cremations, smaller facial bones do not survive, but in this instance, almost all of the woman’s facial structure was recovered and put back together (Liston & Papadopoulos, 2004 pp.15-16).

Impressions of the woman’s face have been created showing what she might have looked like, using the well-preserved facial bones as a guide, as well as information regarding her age, race and height. The jewelry found in her grave was also included in the impression. Visit this link to view the impression of the rich Athenian lady created by Graham Houston as well as her recovered skull.

Click the arrows to view the grave goods found in her grave, along with the urn containing her ashes and the remaining bones (Source; Agora Excavations).

So, now that the bones have been sexed, what can we learn specifically from bones belonging to women from antiquity?

Disease

A variety of diseases can be identified when analyzing bones. Diseases in the body affect the skeletal system and can be evaluated in a lab setting by osteologists and forensic archeologists. The most common disease that affects the skeletal system is osteoporosis, which causes the deterioration and mineralization of bone (Liston, 2012 pp.138; MacKinnon, 2007 pp.496). Women are most likely to suffer from osteoporosis due to the drop in estrogen during menopause, which is a key hormone that maintains bone strength and builds bone (Liston, 2012 pp.138). It can be assumed that women in antiquity suffered from osteoporosis due to this change in hormone activity, but it cannot be identified through recovered skeletons (Liston, 2012 pp.138). It is extremely difficult to differentiate what might be bone degeneration due to osteoporosis or natural post-deposition processes (Liston, 2012 pp.138). Someone who has suffered from a vertebral collapse might have had osteoporosis due to degeneration of the spinal bones, but this cannot be proven by solely looking at the bones (Liston, 2012 pp.138; MacKinnon, 2007 pp.482).

Food intake and preparation influence health and can cause a variety of diseases such as zoonoses, which are diseases transmitted from animals to humans, can occasionally affect the skeletal system and cause deformations on skeletal remains (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). Tuberculosis and brucellosis are two zoonoses that are found within skeletal remains from antiquity (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). Females were generally the ones preparing the food and handling animal meat, which would make them more susceptible to these infections (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). Tuberculosis can cause lesions in the spine which can cause vertebral bodies to collapse (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). Similarly, brucellosis would cause lesions on the vertebrae and sacroiliac joints (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). Scurvy, a disease caused by a deficiency in vitamin C, can also be observed in some bones (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). In ancient Greece, scurvy would have been caused by a lack of fruits and vegetables in the diet (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136). This deficiency would have caused lesions on the mandible, cranium and other flat bones, as well as on the shafts on long bones (Liston, 2012 pp.134-136).

Cancer is a disease that has been researched and identified through skeletal remains from antiquity. Lesions on bones created by tumours can be observed on osteological remains, but are very rare (Irby, 2016 pp.576-577). Evidence of tumours on skeletal remains indicated that all people who lived in antiquity had a chance of developing cancer (Irby, 2016 pp.576-577). A calcified myoma (calcium deposits on the uterine walls caused by the degeneration of benign tumours) was discovered on the remains of a woman from the Late Roman period in Egypt (Irby, 2016 pp.576-577). Another example was the discovery of an ossified ovary teratoma, a type of ovarian cancer, which was found in the pelvic region of a 30-40 year old woman (Irby, 2016 pp.576-577).

A young girl’s remains were discovered by archaeologists in 1994-1995. At the time, a metro station was being built in Kerameikos, Greece, when a mass grave was uncovered and over 150 bodies were excavated (Papagrigorakis et al., 2011 pp.170). Through a series of analyses, it was identified that one of the bodies recovered belonged to an 11-year old girl from ancient Athens and was given the name Myrtis, a common girls name from ancient Greece (Papagrigorakis et al., 2011 pp.169).

Analysis of her remains showed that she had died along with two others who were recovered from typhoid fever around 430 BCE during the Plague of Athens (Papagrigorakis et al., 2011 pp.170). Many bones and teeth that were uncovered from the grave were DNA tested for diseases which revealed the cause of death; typhoid fever (Papagrigorakis et al., 2011 pp.170).

Myrtis’ skull was recovered from the grave and was in very good condition. Her facial bones and features were able to be reassembled and from there, impressions of her face were able to be created (Papagrigorakis et al., 2011 pp.169). A reconstruction of her upper body was created by placing artificial tissues on the surface of a replicated skull. Artificial hair, eyes, and clothing were also added based on what was popular during the time she might have been alive. This reconstruction is on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Read this article for more info on the process of reconstructing her face. For more images of her skull and an in depth dental analysis, visit this page!

Myrtis’ skull (Source; Wikimedia)

Myrtis’ reconstructed appearance (Source; Wikimedia)

The United Nations Information Center used the face of Myrtis during their campaign “We Can End Poverty” and for the United Nations Millennium Development Goals. These campaigns aim to raise awareness for childhood diseases and the importance of supporting research for childhood diseases. Myrtis, a young girl affected by an unpreventable illness as a child, is a perfect symbol and representative for childhood diseases and hopefully learning about her story will compel others to support research. Her story has also been used to promote proper hygiene during the COVID 19 pandemic!

Read more about Myrtis’ life and the Plague of Athens here!

Domestic work

Wear of specific bones have been observed by many archaeologists. Using works of art as well as written sources from antiquity, historians have attempted to make conclusions as to what caused the indentations and wear to form on the bones (Liston, 2012 pp.134). Teeth and surrounding dental bones are excellent examples of this. Teeth preserve well due to the enamel that coats them (Liston, 2012 pp.134). This is what makes teeth strong and durable, which allows them to resist decomposition when buried (Liston, 2012 pp.134).

There have been many discoveries of small indentation on the front teeth belonging to women from antiquity (Sperduti et al., 2018; Liston 2012; Scott & Jolie, 2008 pp.258). The grooves in their teeth were thought to be caused by the utilization of the teeth to cut thread while hand spinning (Liston 2012 pp.134; Scott & Jolie, 2008 pp.258). These types of grooves have been found primarily on teeth that belonged to women, which is how the conclusion that the deformation was caused by hand spinning came to be, as this was a role primarily performed by women in antiquity (Liston 2012 pp.134; Scott & Jolie, 2008 pp.258). Visit this page to learn more about spinning and weaving in ancient Greece!

A study was conducted that evaluated dental remains from Italian excavations from an Eneolithin/Bronze Age cemetery (Sperduti et al., 2018 pp.1). Microscopic evaluations were conducted that showed occlusal and para-occlusal wear in over 3000 dental samples from over 200 individuals from antiquity (Sperduti et al., 2018 pp.1-3). The researchers found that notches and grooves were found in around 60% of the female identified teeth, around 20% of the non-sexed teeth, and only one male-identified tooth had indications of these grooves (Sperduti et al., 2018 pp.4-5). The width of the indentations on the upper teeth suggested that craft activities involving the use of fibres, such as weaving, were the causation of these indentations (Sperduti et al., 2018 –.5).

A similar study was conducted and found similar indentations on dental remains from Norse Greenland. A distinct pattern of wear was identified on 22 anterior teeth belonging to women during 1000-1150 CE (Scott & Jolie, 2008 pp.253). Similar conclusions were made regarding the source of the indentations. The researchers concluded that the way as to which the females at the time manipulated wool and thread, using their canines as scissors generated indentations in their teeth with repeated use (Scott & Jolie, 2008 pp.258).

Trauma

Trauma to the bones can be created by accidents, violence and can offer insight on abuse as well as medical care from antiquity (Irby, 2016 pp.577; Liston, 2012 pp.138). On rare occasions, fractures can be observed in the hands and forearms (Liston, 2012 pp.138). This potentially indicates trauma caused by interpersonal violence (Liston, 2012 pp.138). Cultural practices surrounding violence against women in antiquity could be a possible explanation for a series of fractures (Liston, 2012 pp.138). Osteoporosis could also cause bones to fracture, which may be why women’s bones may have visible fractures (Liston, 2012 pp.138).

The skull of a young woman was discovered from early third century BCE from the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens (Irby, 2016 pp.577). The skull has a piece of metal penetrating the forehead which suggested that the young woman had survived this trauma and lived long enough that the bone and surrounding tissues healed around the point of entry (Irby, 2016 pp.577).

An analysis of injuries to ancient skulls from North West Lombardy archaeological sites was conducted. Computerized tomography (CT scans) was used to analyze the skulls for fractures and traumatic lesions (Licata & Armocida, 2015 pp.251). The data collected revealed that interpersonal violence and weapon-related trauma were the causations of the skull lesions (Licata & Armocida, 2015 pp.252). Two adult skulls belonging to women had antemortem skull trauma – meaning an alteration to the bone right before one’s death (Licata & Armocida, 2015 pp.255). Furthermore, two skulls belonging to women had projectile trauma to the skull which was suspected to be caused by a sling bullet hitting the head (Licata & Armocida, 2015 pp.256). To view the pictures of the skulls visit this link! (Figure 4 in the linked article shows the skull with the projectile indentation)

Conclusion

Now that you have all this information on women’s bones, you may be asking yourself why is any of this important? There is so little information surrounding women from antiquity, and a lot of it has been proven to be biased or unreliable. Bones are lasting evidence of a real person that walked the earth from ancient times and it allows us to have an understanding of their lived experiences. With more research on osteological evidence from the past, historians and archaeologists can continue to learn more about females and their roles in society, and put together puzzles from the past, such as diseases and health patterns that women suffered from.

To produce better work in this area, the study of more bones seems like the best answer, as the more female skeletons we can learn about and analyze, the more connections we can make to the past. However, there are ethical concerns surrounding the disruption of graves and the study of human remains. There is debate on whether it is acceptable or not for archaeologists to “dig up the dead” and archaeologist have tried to figure out when it is okay and when it is not – and there is no clear answer. If you would like to learn more and create your own opinion about these ethical issues here are two articles that discuss this debate:

Peopling the Past – Studying and Displaying Human Remains

National Geographic – When is it Okay to Dig up The Dead?

I hope you have learned something new and will continue to read about and research the women of the past 🙂

“I have no history but the length of my bones”

– Robin Skelton

References

Agora (1967). Cremation burial of a rich Athenian lady. Burial pit (Deposit H 16:6) partially opened showing offerings. At left, cremation area with broken and burned pottery [Photograph]. Agora Excavations. http://agora.ascsa.net/id/agora/deposit/h%2016%3a6?q=rich%20athenian%20lady&t=&v=list&sort=&s=2

Agora (1967). Jewelry from Grave H 16:6. [Photograph]. Agora Excavations. http://agora.ascsa.net/id/agora/deposit/h%2016%3a6?q=rich%20athenian%20lady&t=&v=list&sort=&s=2

Efthimiadis, T. (2010). Myrtis’ reconstructed appearance, National Archaeological Museum of Athens [Photograph]. Wikimedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myrtis#/media/File:Myrtis_reconstruction.jpg

Efthimiadis, T. (2010). Myrtis’ skull [Photograph]. Wikimedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myrtis#/media/File:Myrtis_skull.jpg

Gray. (1918). Female pelvis [Drawing]. Wikimedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelvis#/media/File:Gray241.png

Gray. (1918). Male pelvis [Drawing]. Wikimedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelvis#/media/File:Gray241.png

Irby, G.L. (2016). A comparison to science, technology, and medicine in ancient Greece and Rome. John Wiley & Sons.

Kosma, M. (2012). ‘Princesses’ of the Mediterranean in the Dawn of History: The lady of Lefkandi. 58-69

Leong, A. (2006). Sexual dimorphism of the pelvic architecture: A struggling response to destructive and parsimonious forces by nature & mate selection. McGill Journal of Medicine. 9, 61-66 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2687900/

Licata, M., & Armocida, G. (2015). Trauma to the skull: An analysis of injuries in ancient skeletons from north west Lombardy archaeological sites. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 13(2): 251-264 Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27604196/

Liston, M. (2012). Reading the bones: Interpreting the Skeletal Evidence for Women’s Lives in ancient Greece. Doi: 10.1002/9781444355024.ch9

Liston, M., & Papadopoulos, J.K. (2004). The “rich Athenian lady” was pregnant: The anthropology tomb reconsidered. Hesperia 7-38 Available from: https://ezproxy.acadiau.ca:9443/loginqurl=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3182017

MacKinnon, M. (2007). Osteological research in classical archaeology. American Journal of Archaeology. 111(3), 473-504 Doi: 10.3764/aja.111.3.473

Mauzy (1985). Early Geometric jewelry found in a burial. A pair of gold earrings with filigree and granulation and pomegranates pendant (J 148) and a necklace of glass and faience beads (J 149, G 587-591) [Photograph]. Agora Excavations. http://agora.ascsa.net/id/agora/deposit/h%2016%3a6?q=rich%20athenian%20lady&t=&v=list&sort=&s=2

Mauzy (1985). Geometric pottery from the cremation burial of a rich lady, ca. 850 B.C. Deposit H 16:6. From left to right: granary (P 27646), small olpe (P 27633), amphora (P 27629) with cup as cover (P 27636), pyxis (P 27634), olpe (P 27631), basket (P 27641) and smaller amphora (P 27630) with cup (P 27635). [Photograph]. Agora Excavations. http://agora.ascsa.net/id/agora/deposit/h%2016%3a6?q=rich%20athenian%20lady&t=&v=list&sort=&s=2

Nguyen, M.L. (2011). Ancient Greek sling bullets with engravings. One side depicts a winged thunderbolt, and the other, the Greek inscription “take that” (ΔΕΞΑΙ) in high relief [Photograph]. Wikimedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sling_(weapon)#/media/File:Sling_bullets_BM_GR1842.7-28.550_GR1851.5-7.11.jpg

Papagrigorakis, M.J., Synodinos, P.N., Antoniadis, A., Marvelakis, E., Toulas, P., Nilsson, O., & Baziotopoulou-Valavani, E. (2011). Facial reconstruction of an 11-year-old female resident of 430 BC Athens. Angle Orthodontist. 81(1), 169-177 Doi: 10.2319/012710-58.1

Scott, R.G., & Jolie, R.B. (2008). Tooth-tool use and yarn production in Norse Greenland. Alaska Journal of Anthropology. 6(1), 253-264 Available from: http://www.alaskaanthropology.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/akanth-articles_252_v6_n12_Scott-Jolie.pdf

Sperduti, A., Guiliani, M.R., Guida, G., Petrone, P.P., Rossi, P.F., Vaccaro, S., Frayer, D.W., & Bondioli, L. (2018). Tooth grooves, occlusal striations, dental calculus, and evidence for fiber processing in an Italian Neolithic/Bronze Age cemetery. American Journal of Anthropology. 1-10 Doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23619

The article was very well written. One of the parts that stood out to me as I was reading was the connection to modernity and how Myrtis was used as part of the campaign from The United Nations Information Center to raise awareness for childhood diseases and importance of supporting research for childhood diseases.

LikeLike