Studying children and childhood is of great importance because it provides insight into social norms and social life in ancient Greece. Children were important for the parents, the home, and city. Not having children led to inability to pass on the property and wealth of the father. Women, especially from high-status families, were used for diplomacy between their natal family and the family they entered when they got married; as part of this arrangement, they were expected to become mothers. Men were the representatives of the family in the outside world and were the “kings” of the household. Myths, art and poems all contribute to the comprehension of childrearing and children’s status in the complex community of the Ancient Greeks.

Fertility rituals and importance of producing offspring

Having children was really important for Ancient Greeks. Therefore, women participated in rituals that were supposed to help them with their fertility and ability to bear children. One of the most famous festivals for fertility is the festival of Thesmophoria (Figure 1) where only married women could participate.

During Homeric times, the economy was mainly formed around agriculture and having more children meant having more helpers with the work. Girls were considered most useful to society when they became mothers. Illegitimate children were accepted, however, as they would be of extra help [1]. Therefore, the bonds between the parents and the child were extremely strong and losing a child was unbearable to them. Sons were expected to take care of their parents when they became old and ill.

Homer’s Iliad, is not in any sense about children, but it shows the connection that parents had with their sons and daughters during Homeric times. The poem’s overall structure and conclusion ultimately suggest the sacrifices that parents made for their children [5].

“Then taking up his dear son, [Hector] tossed him about his arms, and kissed him, and liften his voice in prayer to Zeus the other immortals: … and someday let them say of him: ‘He is better by far than his father’.”

Iliad 6.466-486

This scene shows the bond created by the father and the son (Figure 2); Hector prays his son will be better than himself- his goal is to ensure his son will be recognized by the gods as a great warrior for his dedication to the state.

In Athens, children were looked at as heirs of the estate, thus they were really important to the family. The newly born was not always accepted, contrary to the Homeric times, as it was not a crime. The father decided if he would accept the child or abandon them, leaving them in front of a temple [1]. Boys were more useful to the families and therefore it was more often for the rejected children to be girls rather than boys.

Symbols of birth and welcoming the newborn

The birth of a boy was announced to the city by placing an olive wreath on the door which symbolized that one day he would become a great warrior and maybe sacrifice his life for the better of the state. When a girl was born, they put a knot of woolen thread on the door, symbolic of her expected future to be a housewife and be responsible for weaving, taking care of the house.

The baby that was accepted by their father was bathed in oil and water and wrapped in woolen cloth [1]. Ten days after the birth, the child was finally officially recognized by the father and was given a name selected by him. Boys underwent additional ceremonies which helped them get prepared to gain citizenship status in the future. Girls could not partake in such rituals, which shows the weaker connection they had with the household which led to easier transition into the new family when they got married [4].

Similarities and gendered differences

Boys and girls grew up together until the age of 7, playing the same time of games and residing in the women quarters (gynaeceum) of the household together with their mother. They used the same toys to play, more interesting of which were alive beetles they would tie at one end of a string and run while holding the other end. There is evidence in Athenian iconography that suggests some toys were considered gender appropriate- dolls for girls and hoops for boys [2]. It is possible that these were only artistic means of representing if the child in the painting was female or male since we know that in their early childhood, boys and girls lived together and were more often looked like playful children than gendered members of society.

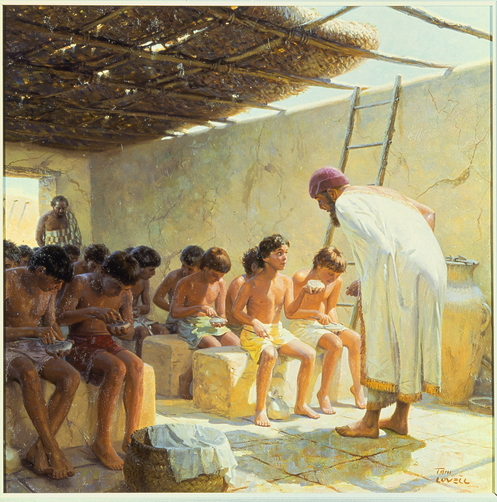

Once they became of age seven, separation between the genders was seen and they no longer played together. Boys were encouraged to play tug of war, play with balls and other games that prepared them for their future training to become warriors. Additionally, they went to school (Figure 3), contrary to the opposite gender, where they received education that would help them develop the needed qualities to become citizens and part of the state government.

For Spartans, militarism was more important, that’s why even girls received military training (talked about in detail later). For Athenians, it was important that the boy was both intellectual and athletic [1]. Education was a responsibility of the parents- he could be taught at home or sent off to a private school.

Boys didn’t usually continue their education after the age of 15 but if they did, they entered the gymnasium at 16 for two years. After the two years at the state school, they had to practice a ritual which included a wine party where they cut their long hairs in sacrifice to Apollo. Then, boys could finally be presented as candidates for citizenship by their fathers. Once accepted, they received two or three years of military training- the final step on receiving full citizenship of the state.

Contrary to the way boys were trained and educated after the age of seven, girls received their training at home- they were taught to sing and dance (which was really important for girls to know how to do as one day they might become entertainers), learnt how to do embroidery, spin, weave and cook. They could not receive any form of education- women remained illiterate in the world of Ancient Athens. Girls could not become citizens either- they were only trained to be housewives and were married as soon as they could bear a child- around the age of 15.

Things looked different in Sparta. From their birth, both girls and boys were prepared to be healthy strong warriors of the state. In order to produce physically superior children, girls were required to go through the same training that boys went through. Spartan girls took part in public games and contests which required physical strength and speed. When participating in such activities, girls had to be naked to show their powerful bodies and how worth it all of those training were in order to make them strong and able to give birth to healthy warriors (Figure 4).

Adoption

When respected Ancient Greek families could not have male children, it was common to adopt. One of the daughters would get married to the adopted son who would inherit the estate. This shows how important inheritance was for the Greeks. Athenian women could not receive any part of the husband or father’s wealth. It was only sons or close family male relatives who could inherit. Even the mother or wife of the deceased did not have the right to take over the estate.

Ancient myths

Studying the myths and beliefs of Ancient Greeks represented in their art gives an additional insight into the subject of children and childhood. There is a gendered difference between the way gods and goddesses looked when they were born- gods, such as Hermes and Dionysus, were portrayed as infants, whereas goddesses like Athena and Aphrodite were shown as fully grown adult women(Figure 5). It is believed that the reasoning behind all of this is the fact that as the society was patriarchal and men were believed to be superior, the divine boys had the opportunity to grow into adults in the course of their lives and become the best version of themselves [3].

Studying children and childhood is a great way of understanding how the society was built and what were the accepted norms in raising girls and boys. Depending on what part of Greece is looked at, there were differences but also a lot of similarities in the life of young boys and girls, who were prepared to adopt their expected gender role in their adult life

Here’s a video by Digital Diogenes on YouTube that gives some additional information on the Ancient Greek family:

Bibliography

[1] Bardis, P. (1964). The Ancient Greek Family. Social Science, 39(3), 156-175. Retrieved September 28, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23907609

[2] Beaumont, L. A. (2012). Childhood in Ancient Athens: Iconography and social history. ProQuest eBook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uma/reader.action?docID=1114632

[3] Cohen, A. (2007). Gendering the Age Gap: Boys, Girls, and Abduction in Ancient Greek Art. Hesperia Supplements, 41, 257-278. Retrieved September 28, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20066793

[4] McClure, L. (2019). Women in Classical Antiquity: From Birth to Death.

[5] Pratt, L. (2007). The Parental Ethos of the Iliad. Hesperia Supplements, 41, 25-40. Retrieved October 24, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20066781

Additional useful and interesting sources

- Thesmophoria – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thesmophoria

- Homer’s Iliad – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iliad

- Hector – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hector

- Ancient Greek Toys – https://www.coolaboo.com/world-history/ancient-greece/ancient-greek-toys/

- Goddess Athena – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athena

2 thoughts on “Children and Childhood in Ancient Greece”